A long and painful year finally closed with a whimper on December 30, 2022.  After reaching an all-time high on the first trading day of 2022, the US stock market declined sharply if unevenly throughout the year. Patient, diversified investors weren’t spared the pain, however. 2022 was the worst year of performance EVER for the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index. It was only the third time since 1926 that stocks and bonds both fell in the same year (so much for diversification) and it was the first time that both asset classes suffered declines of more than 10% in the same year.

After reaching an all-time high on the first trading day of 2022, the US stock market declined sharply if unevenly throughout the year. Patient, diversified investors weren’t spared the pain, however. 2022 was the worst year of performance EVER for the Bloomberg US Aggregate Bond Index. It was only the third time since 1926 that stocks and bonds both fell in the same year (so much for diversification) and it was the first time that both asset classes suffered declines of more than 10% in the same year.

As we review the year that was and endeavor to learn lessons that can be applied to 2023 and beyond, there are no shortage of causes for the terrible returns of 2022. We will discuss a number of them in the pages that follow, but our candidate for the top spot is inflation. At the end of 2021, the Fed finally noticed inflation and decided it wasn’t transitory. By the time this discovery led to action with a 25 basis point interest rate increase in March, the inflation horse had already bolted the economic barn and the Fed was far behind the curve in addressing the problem. It took readings of more than 9% in annualized inflation for the Fed to begin to move more aggressively with a series of four 75 basis point rate hikes and a total of 425 basis points in seven months. By year’s end, we had experienced the sharpest increase in rates in US economic history. This did seem to be having some impact on the financial markets, but progress on inflation is proving harder to discern.

We cannot emphasize how important this is. Reasonable people can debate the causes and cures for inflation, but a stable inflation is a prerequisite to sustainable economic growth and sound financial markets. Until that stability is achieved, we will likely continue to oscillate between seemingly irrational greed and fear.

The Year in Review

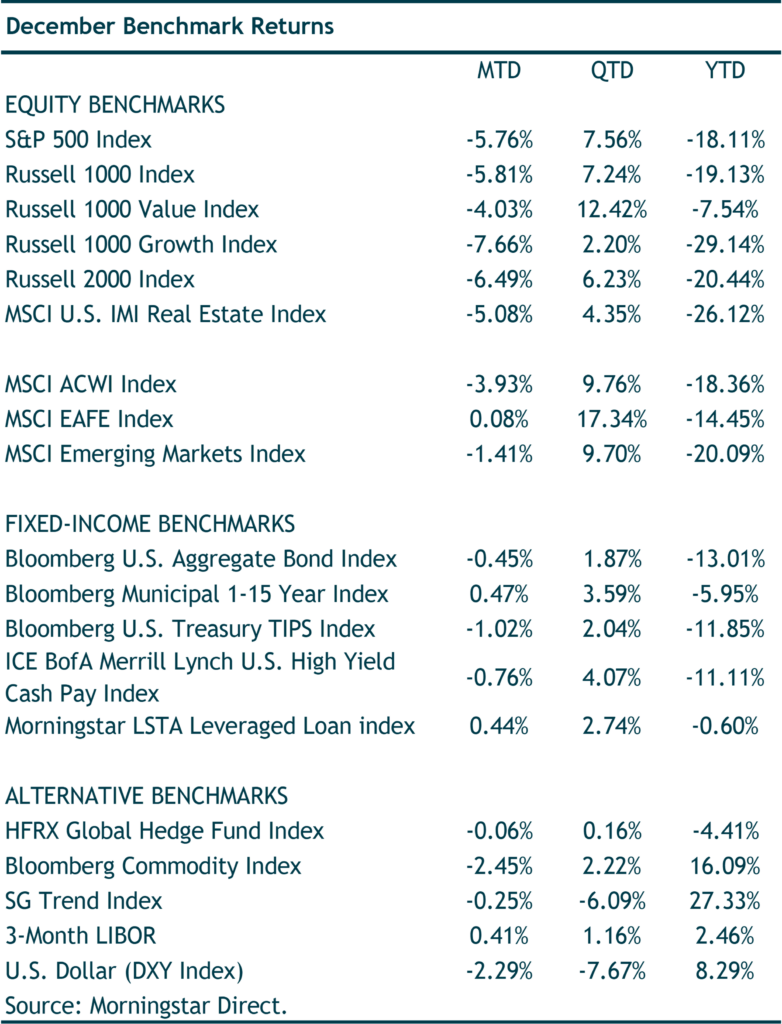

As detailed in the chart above, it is challenging to find enough superlatives to describe how difficult the markets were for investors in 2022. While commodities provided solid returns, simple cash outperformed stocks and bonds by more than 15%. Unprecedented was an overused word in the past three years, but it certainly seems to apply to financial markets in 2022. The causes were many.

Clearly, the breakout of global inflation, and the resulting central bank policy response, was the most important financial story of the year. When the great financial crisis unfolded in 2008, global fiscal and monetary policy moved with remarkable coordination to stave off the financial “emergency” and avoid a second great depression. We will never be able to evaluate the counterfactual (what if policy makers simply let nature take its course?) and there aren’t many critics, even today, who think the actions of 2008 and 2009 were wrong. Where critics are increasingly in agreement, however, is that the emergency actions of 2008 and 2009 continued for more than a decade unnecessarily. Can you have an emergency that lasts twelve years?

Skeptics didn’t think an emergency could last that long. Most were of the view that the combination of massive fiscal deficit spending coupled with zero interest rates and its successor, quantitative easing, would create inflation. Remarkably, though, inflation stayed at bay. Not surprisingly, the ability to spend money and print money seemingly without limit or consequence emboldened both politicians and policy makers who always find it easier to say yes than no. What had seemed impossible to conceive in 2008 (i.e., a one- time $30 billion support for JP Morgan to bail out Bear Stearns), gave way to $30 billion per WEEK of government bond purchases in the US beginning in March of 2020 in response to Covid.

Perhaps this level of monetary stimulus would, on its own, have driven inflation higher. However, two other developments coincided with this monetary bacchanal. The first was the impact of Covid. We firmly believe that the impacts of Covid and the policy responses will be with us for years. Over time we will continue to understand the impact on public health, mental health, educational achievement, confidence in institutions and social cohesion. Economically, however, the Covid lockdowns resulted in two important developments.

Supply chains were severely disrupted. The West discovered that outsourcing all of your manufacturing, for everything from PPE to Advil to semiconductors, can leave you vulnerable. As China continued to deal with Covid via the just repealed zero Covid regime, the long shadow of supply disruption clearly contributed to inflation for goods. More significantly, Covid reduced the supply of available workers. Some workers got sick and didn’t recover. Others left the workforce to care for a family member or school age kids. Others didn’t want to where a mask to work. Some didn’t want to get a vaccine shot to come to work. The stories vary, but the result is the same: we now have a chronic shortage of employees in nearly every segment of the economy. For the few and the proud who remain at work, they have the ability to command higher wages and compensation. Demographics and the retirement of baby boomers had us trending in this direction, but Covid pushed the process forward and it doesn’t look like we are going back to the “good old days” soon. Thus, we are concerned that labor shortages and wage pressures will continue to make inflation hard to control. And the Fed can’t “print” more workers to fix this problem.

The second key development that contributed to the inflation breakout was the profligacy of the Federal government. When the Covid lockdowns began, the Federal government (with a Republican President and Senate), unleashed spending to support the economy that led to a deficit of more than $3 trillion in a single year. Not since the World War II had deficit spending been such a large percentage of GDP. Not to be outdone, in 2021 the new Biden administration and a Democratic Congress passed two massive spending bills (The American Rescue Plan and the Infrastructure Bill). These bills passed despite the recovery of GDP to pre-pandemic levels and unemployment at 3.5%. The deficit was more than $2 trillion and no credible forecast sees deficits declining below $1 trillion annually. Importantly, the full impact of spending from the infrastructure bill has yet to be felt because as we learned in 2009, there aren’t many “shovel” ready projects to be funded quickly.

This toxic cocktail of monetary and fiscal largesse, coupled with the pandemic impact would likely have made inflation a problem without a boost from geopolitics. However, on February 24, Russia invaded Ukraine. The post- World War II global security order that developed after the collapse of the USSR was gone in an instant. The conceit that economic ties would prevent the sort of carnage that consumed the globe in the 20th century was shown to be folly.

In its place, the world learned that if you were concerned about the supply chain disruptions of Covid, you ain’t seen nothing yet. Europe, which had come to rely on Russian energy, suddenly found itself without a plan B. Food insecurity became a major worry as we learned that the Ukraine was one of the world’s major grain exporters. War is and always has been inflationary and the current “special military operation” is no different.

The human toll of the conflict is horrible. All wars end and we hope for a rapid end to this conflict. If a truce were announced tomorrow, financial markets would react with glee. However, as with Covid, we don’t think we are going back to the antebellum state of affairs. Russia is surely weaker than prior to the invasion and a weak autocratic regime armed with nuclear weapons should worry the entire world. The alliance between Russia and China is stronger than it has been at any time in recent memory and that is not something that works in the favor the US or the West. Whenever the shooting stops, the cost to rebuild Ukraine and who bears that cost will come into focus as the next economic challenge for the world.

High inflation, rising interest rates and geopolitical tensions, taken together create a difficult environment for risk assets. However, to suffer the real pain that investors felt in 2022, it takes one more key element and that is excessive valuations. And we had those everywhere you looked at the beginning of 2022.

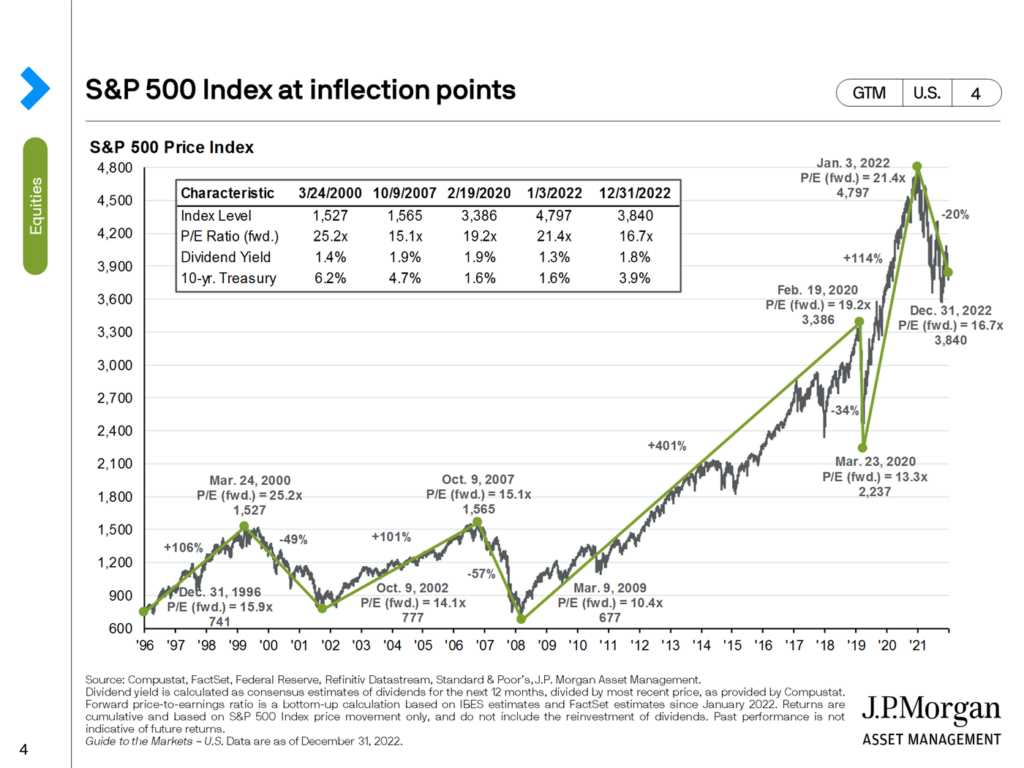

As the chart on the previous page from JP Morgan notes, when the S&P 500 hit its peak on January 3, the PE ratio was higher than at any other market peak except for the dot com bubble. Dividend yields (always a key component of equity returns) were lower than at that same peak. Just as importantly, interest rates were at the lowest levels that investors could recall. The bottom line is that there was ample room for prices to fall and they did with PE ratios falling from 21.4 to 16.7. That valuation decline explains the market decline in 2022.

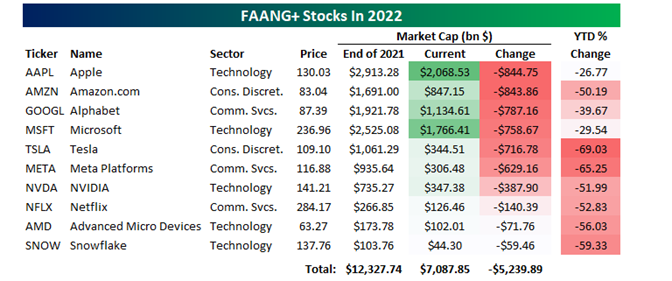

There are three more specific examples of richly valued assets falling back to earth in 2022. Most prominently are the high- flying tech stocks known as the FAANGs (with varying acronyms). Like the nifty fifty stocks of the early 1970s, which were great businesses and market leaders at the time, investors became so enamored of the names that they concluded that the stocks simply had to be owned at any price. Value didn’t matter, they said, if you had a great business making money. When the Fed began raising rates in 1973 in response to inflation and high oil prices brought about by the first Arab oil embargo (sounds familiar), the nifty fifty crated and many of the stock never returned to their al time highs. In 2022, the FAANGs suffered a similar fate as detailed below. We don’t know what the future holds for these names, but the takeaway must be that value matters always and everywhere when you invest.

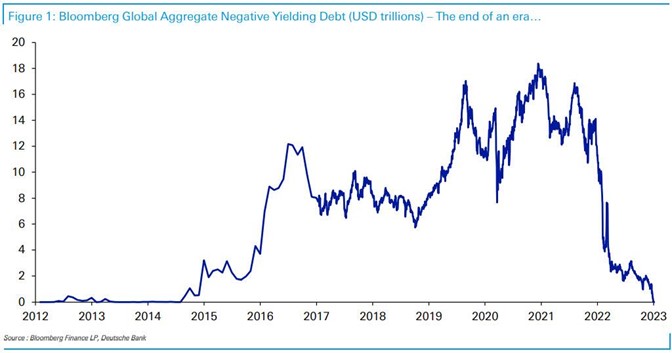

Arguably, the bubble that developed in the tech names was due to low interest rates. Central banks the world over first took policy rates to zero and then proceeded to print money through quantitative easing. The goal was to stimulate economies but they seemed to have done a better job of stimulating markets. While reasonable people can differ about what the “correct” level of interest rates should be, it is hard to make the case for negative interest rates. The idea that an investor would defer current consumption or use of their cash, and instead pay a government to hold their cash for them, seems absurd on its face. However ridiculous this seems, however, it was the reality for many bond markets since 2014. The farce, however, has finally ended. In the first week of January, the last negative yielding bonds in Japan traded back into positive yield territory. As the chart from Deutsche Bank notes, at the peak there was $18 trillion of negative yield bonds. We would never say never, but from our vantage point this seems unlikely to be repeated.

Finally, the implosion of crypto currencies in 2022 strikes us as another good example of value mattering. We remain sympathetic to the argument that there is a place for an alternative currency. Because a currency needs to be a store of value, a unit of account and a medium of exchange, creating one out of thin air and anointing it with a value seems to us a logical stretch. Our view seemed quaint and old fashioned in November 2021 when the aggregate value of crypto currencies exceeded $3 trillion (more than the value of Apple, and considerably more at that time than the value of all US energy stocks). Fast forward one year, and rising rates drubbed values by more than 75%. And then FTX happened.

We have followed and read with great interest about the unfolding debacle at FTX. The details matter, but the overarching theme has been replayed throughout financial history more times than we can count. Greed coupled with novelty always sets up poorly. When you had in an epic amount of hubris and a complete vacuum of rules and controls, you end up with what will go down as one of the largest and most public frauds in history.

The common thread to each of these valuation crashes is the impact of rising interest rates. When interest rates are low and flat, investors reach for returns and often abandon caution and common sense. From our standpoint, that has made much of the post GFC world so vexing. With raises now up off the floor and rising, we suspect that the return to fundamentals that we have long hoped for will continue. With that hope, we humbly turn our attention to expectations for 2023.

The Year to Come

While the exercise of looking ahead is vital for investors, it is an exercise that demands humility. At this time last year, Wall Street consensus was that inflation was a modest problem that would be addressed with interest rate hikes up to 2%. Suffice to say, getting that forecast wrong made every other prognostication from the Street irrelevant in 2022.

For 2023, if there is a consensus, it is that the Fed has done most of the heavy work on inflation. An inverted yield curve (i.e., short rates higher than long rates) has always led to a recession, so most forecasts anticipate a mild recession that will allow the Fed to pause rate hikes or even pivot to rate cuts. In this view, corporate earnings struggle in the first half of the year but rebound in the second half. This rewards the patient investor.

While the consensus is sometimes correct, we get nervous when we see that level of unanimity. This prompts us to wonder how the forecast could be wrong.

The more distressing possibility is that there is a severe recession. Economists are notoriously slow in catching up to bad news during a downturn. If we do have more than a mild recession, it seems likely that inflation will decline. That would give the Fed room to pause and perhaps cut rates and make bonds a solid performer. The bad news is that corporate earnings will too. Using history as a guide, we could see earnings fall to $175 per S&P 500 share. Applying a 15 PE would produce a trough value of 2,625 for the market. That is well below current levels and would imply a further equity decline of 25% from where we sit today. That isn’t a forecast nor is it our expectation. Instead, it is an important exercise to go through as we consider risk and reward.

We suspect that the more likely error will be in underestimating the economy. Despite nine months of rising rates, economic growth actually seems to be accelerating by some measures and the job market remains strong. Can you have a severe downturn with a 3.5% unemployment rate and nearly two job openings for every unemployed worker? Our thesis has been that QE didn’t do much for the economy, but it did goose the markets. Its inverse, quantitative tightening or QT, may hurt financial assets (as we have seen in 2022) but not harm the economy much. If this plays out, the Fed will likely need to press rates higher and leave them higher for a longer period than investors might like. In the long sweep of history, rates at current levels aren’t the end of the world. The journey to those levels can be painful, but the destination isn’t all bad.

To that end, the best news of a dismal year is that we can now earn decent returns on cash. With 6 month T bill yields approaching 4.8%, it appears that the days of savers suffering with zero returns may be over. With all of the economic and geopolitical uncertainty, these returns strike as attractive on a risk- free basis.

In the risk asset markets, we think that cheap remains better than expensive. And the ability to generate real cash flow today is vital. Valuations have corrected meaningfully across many assets, but for some (think unprofitable tech names), the pain probably isn’t over. Conversely, we are becoming more interested in US small cap stocks that should benefit from a move to reshoring of production and a more balanced domestic economy. We also continue to find resource stocks attractive given compellingly cheap valuations. Finally, with the dollar seemingly having peaked, foreign stocks continue to look cheap.

We say the same thing at the beginning of each year. If you had invested $100 in US equities in March 2008 at the dawn of the financial crisis, it is now worth $288. That same $100 invested in non-US equities is only worth $94. Fifteen years of Fed stimulus created that disparity, but if the Fed is acting differently, will that gap close? It is worthy of consideration.

Bonds offer a more balanced risk reward profile than they did a year ago. In a weak economy, high quality fixed income may offer the portfolio ballast that it has historically. That said, with our bias to a decent economy and potentially more Fed tightening, we continue to favor T bills over longer duration bonds.

Tax Planning for 2023

The start of a new year always gets us thinking about taxes. At the end of 2022, in an embarrassment of poor governance, Congress passed an “Omnibus” spending bill that ran more than 4,000 pages and was unread by anyone voting on it. Predictably, it included a grab bag of goodies. There are a number of important tax law changes in the bill including pushing the required beginning date for RMDs to 75. We are working our way through the provisions and will plan on updating you as the details become more clear.

In the meantime, we encourage you to begin accumulating income tax information as it arrives. While being early to most endeavors is good, that isn’t the case when filing your tax returns. Because much of the 1099 reporting for your portfolio is subject to correction, we would recommend waiting until later in February or even March to see if any corrected 1099s arrive. That can save the aggravation of correcting or amending a return later.