The first quarter of 2025 will go down as the quarter of sharp reversals. As the year began, investors were looking ahead to the incoming Trump administration and its myriad campaign promises. As when Joe Biden took office with the goal of reversing nearly every policy of the first Trump administration, Trump 2.0 planned on returning the favor. Thus far, the whipsaw has only surprised in its reach and vigor. Partly in response to these changes, financial markets also whipsawed sharply in the quarter.

The US stock market, which ended 2024 on a soft note, rallied into inauguration day. It was quite the spectacle to see the titans of technology lined up for the indoor inauguration. Whether they were present because of the “vibe shift” or were trying to curry favor with the new administration, it couldn’t have been a more different view than the first Trump inauguration. Shortly after the big event, President Trump held a White House presser where he announced huge investment commitments to infrastructure and data center construction in the US. It is remarkable how close in time this press conference was to the late January announcement by a Chinese company of their new, vastly cheaper AI engine called Deep Seek.

Perhaps it was the Deep Seek announcement that turned stocks around. Or it could have been the new administration’s rhetoric about tariffs. We have more to say about tariffs and their implementation below, but February marked the beginning of erratic pronouncements about tariffs for both friends and foes. It was challenging to keep track of what was announced, rescinded, modified, postponed, and reinstated.

That is not precisely the landscape that arouses animal spirits for management or investors.

Alternatively, it could be that investors were discouraged by the suddenly reticent Federal Reserve. Last September, the Fed deemed the economic outlook dire enough to warrant a 50‐basis‐point interest rate cut less than two months before the election. They followed with cuts in November and December, but as 2025 dawned, the Fed signaled a desire to stay on the sidelines. For investors who had become accustomed (addicted?) to falling interest rates supporting high asset prices, the newly prudent Federal Reserve had suddenly removed a key prop for the bull market in everything.

Whatever the combination of factors that shook sentiment, markets reacted sharply. After reaching all‐time highs for the S&P 500 and NASDAQ on February 19, both indices experienced technical corrections with declines of 10% and 13%, respectively, within a month. While late March offered a modest bounce back, for the quarter, the NASDAQ ended down more than 10%. Interestingly, it was the Magnificant Seven stocks (those over‐owned and overloved tech giants) that led the way with a weighted 15% decline in the quarter.

Interestingly, foreign markets fared much better, with both developed and emerging markets outperforming the US. Some of this was tied to better valuations, but much of the catalyst did come from the new Trump administration. For the moment, its apparent hostility to Europe and calls for greater European defense spending seem to be catalyzing change on the continent. The Germans’ elimination of their “debt brake” to allow for more significant fiscal stimulus and defense spending highlighted the change. Now, they must follow through.

Bonds also saw sharp reversals. The benchmark ten‐year Treasury yield was approaching 5% in mid‐January, but yields ended the quarter at 4.23%. Typically, lower long‐term rates are supportive of the economy and the markets, but investors in risk assets seem unable to focus on this positive aspect among all the other news and developments.

With changes in government, sharp reversals in policy and personnel, equity market leadership shifting away from the US and the “Magnificent Seven,” and longer‐term interest rates drifting downward, this was truly a quarter of massive reversal. As we learned, however, this was merely a tune‐up for the surprises of “Liberation Day.”

Thoughts on Tariffs and Liberation Day

One of the oldest and most often cited pearls of investment wisdom is that “markets hate uncertainty.” It is said so frequently, including by this author, that it must surely be true. But if you step back and consider it for a moment, it may be one of the most useless platitudes ever uttered.

We live in an uncertain world. Every day that we wake up and venture from home, life throws us curveballs, from bad weather to bad traffic. Some days begin with fender benders, and for an unfortunate few, some end with catastrophic accidents. Who is to know what the future holds? Who has certainty about anything other than death and taxes?

As investors, this is equally true. From conflict to peace, from global pandemics to clashes over trade policy, no one ever has certainty about their investments. We live in dread of the fickle perils of fate, but we often forget that, with certainty, man wouldn’t have learned to fly or invent today’s technological wonders.

Today’s certainty is tomorrow’s chaos. The world in which we live and invest is being endlessly shaken and stirred. As comforting as it is to have certainty, for investors, certainty guarantees the modest return of a short‐term Treasury security pressed to keep pace with a rising cost of living.

We share those observations because we prefer the uncertainty that existed before Liberation Day. While the discussion of punitive tariffs was a focus for markets, the thought was that whatever actually went into effect wouldn’t be that bad. Alternatively, it was thought that the threat of tariffs was a gambit for negotiations to set up more favorable trade terms for the US. Whatever the reason, investors were ill‐ prepared for the announcement of far more punitive tariffs with a far greater reach. We now have a lot of certainty about this topic, but we preferred the uncertainty of April 1 to the certainty of April 3.

We believe in free people and free markets, and we don’t like tariffs. We appreciate the objectives of the administration in imposing tariffs; however, we ultimately believe they are counterproductive.

Unfortunately, we weren’t asked to opine on the topic for the Liberation Day Rose Garden event, so we are left to grapple with the impact and navigate a path forward.

During the lead‐up to the 2020 election and throughout the Biden Presidency, we were early, consistent, and persistent critics of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). In loose terms, MMT posited that deficit spending didn’t matter. A country with a reserve currency, such as the US, could print and borrow limitless sums, spend wildly, and not suffer any consequences. It is an idea so ridiculous that only academics could embrace it. Unfortunately, it was a misguided idea that gained momentum during the Biden years with the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act and the accompanying deficit spending of that time.

We were of the view that this deficit spending, more than interest rate policy or COVID lockdowns, propelled inflation higher. Because the government has continued to run deficits of more than $2 trillion per year, it is no surprise that inflation hasn’t been brought under control.

The premise of MMT was farcical on its face, but we were also struck by the idea that if being a rich country only required running the printing press, why hadn’t this been tried before? Surely, an idea this compelling had been tried and been successful? While versions have been tried, you can’t find anyplace that has had success with this folly.

Using tariffs to fix other underlying economic problems strikes us as a similar fool’s errand. If tariffs are only paid for by “others”, then why stop at 10%, or 34%, or 54%? Shouldn’t we just impose tariffs and cover all of the operating costs of our government? After all, having someone else pay for something can be really liberating. Once again, the painful truth is that tariffs act as a tax on trade. If you want less of something, tax it. That is what we will get as the tariffs are imposed.

The Goals for the Tariffs

We applaud the goals that the administration is trying to achieve. The broad view is that the US manufacturing base has been hollowed out over the last fifty years. It is hard to argue with that. During the COVID lockdowns, we witnessed in real‐time how dependent we were on certain potential adversaries for key economic inputs, ranging from rare earth minerals to pharmaceuticals and semiconductors. The most fundamental goal of the tariffs is to encourage (with a stick) the reshoring of manufacturing.

If this succeeds, it will also have the virtue of creating US jobs. Everyone is for this, but we aren’t sure that a return to the glory days of US manufacturing in the 1950s is even possible. The nostalgia for the glory days is admirable, but it may be hard to achieve a rebuild of the middle class with tariffs.

The administration also wants trade on more fair terms. Everyone supports free trade, but there aren’t as many proponents of fair trade. Because fairness and beauty are in the eye of the beholder, this is a more nebulous goal. The administration makes a very legitimate point that many countries impose a combination of tariffs and other trade restrictions that are far higher than we impose on them, and this, in turn, hurts the US. That doesn’t mean, however, that every country that runs a trade deficit is harming us. Trade isn’t a zero‐sum game, so we think that a case for reciprocity in tariffs is defensible.

Tariffs are also being used as a tool of statecraft. The best example is the pressure being brought to bear on both Mexico and Canada to assist in reducing the flow of illegal immigrants and drugs to the US. Whether this is the best tool for the job, it appears to be the tool of choice for President Trump.

Finally, the administration believes that tariffs will help to address the US fiscal situation. We are on an unsustainable path. The administration claims that they will raise $600 billion per year from their tariffs. Over a decade, this would make a meaningful dent in our deficit, all other things being equal. Historically, critics of tax hikes point out that economic behavior changes in response to the penalties or incentives inherent in tax changes. Thus, higher marginal rates rarely generate as much tax revenue as proponents hope. We would suggest that this same analysis likely applies to these huge tariff increases. Higher tariff rates will be applied to a lower base of activity, thwarting at least some portion of the anticipated revenue haul.

Additionally, much of the revenues will be diverted to shore up those impacted by higher tariffs. For example, there is already a discussion of subsidies for farmers who have seen retaliatory tariffs hit their end markets. This sort of giving and taking is enormously economically inefficient.

If our skepticism is misplaced, and the administration succeeds, they will have fundamentally altered the global trade system that grew up in the eighty years since the end of WW II. We hope for the best but are dubious.

Economic Impact of the Tariffs

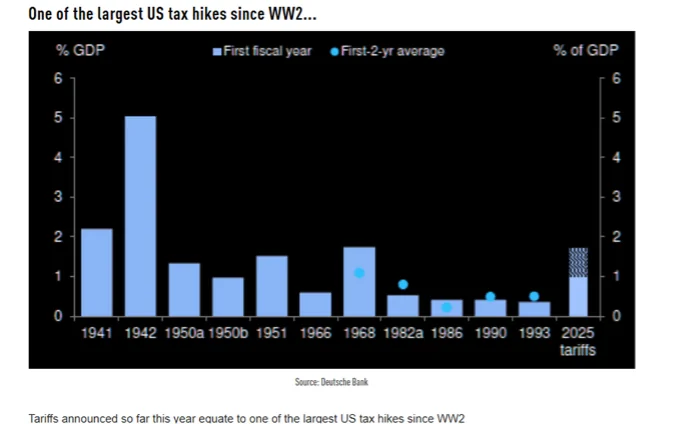

If the administration realizes its goals from this dramatic policy shift, the evidence will unfold over years and decades. The challenges, however, are more immediate. Tariffs will act as a tax hike, slowing the economy. As Deutsche Bank notes, this is effectively one of the most significant post‐war tax hikes in US history. At the same time, until supply chains adjust, it will act as an inflation shock that pushes up prices. Most credible forecasts that we have reviewed suggest a 1% to 1.5 % hit to GDP. This may not be enough to push us into recession, but it clearly increases the chances of one. On the inflation front, we can expect a 1% increase in inflation in the coming year.

Against this backdrop, the Fed is in a pickle. Slower growth would suggest that rates should come down, but higher inflation would argue for higher rates. It isn’t hard to imagine Jerome Powell sitting on his hands and counting the days until his term as Fed chair ends in May 2026.

Regardless of what the Fed does, longer‐term rates have gone down in a flight to quality. The ten‐year Treasury is back below 4%, and oil prices have fallen on recession fears. Both should offset some of the stagflation impulse from the tariffs.

What should an investor do?

There are many superlatives that can be applied to the market sell‐off following Liberation Day. The VIX, a measure of volatility, closed at its highest level since the COVID‐19 selloff and crisis. The two‐day decline was in line with market reactions during the COVID‐19 crisis, the Great Financial Crisis, and the Great Depression. While this isn’t the company you want to keep, some perspective is in order.

The market is of the view that tariff changes are bad. Unlike an unknown and unseen virus wreaking havoc and death or a global financial meltdown due to bad loans that spread around the world, this trigger is a policy change. It could be reversed tomorrow. It could be reversed in a year or in four years. To the extent it doesn’t work, we suspect it will be changed. This simple fact says to us that the emotional overreaction has gone too far.

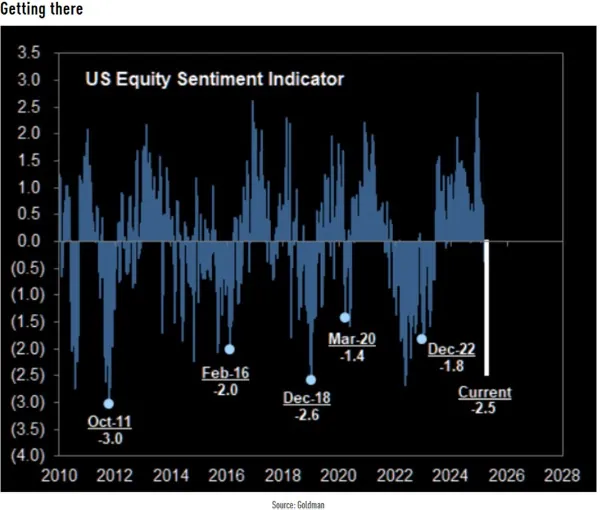

Emotional overreactions can go even further. We have no idea what the coming days or weeks will hold. We do know, however, that sentiment has fallen to deeply pessimistic levels. These levels have, in the past, marked great entry points for investors. We aren’t pounding the table to buy risk assets today, but you have to be more interested. If you loved the Mag Seven three months ago, surely they are more interesting at 30% off? At the same time, we develop long‐term plans and strategies to get through difficulties and unexpected markets. The speed and severity of the selloff suggest that abandoning risk assets today is a poor choice.

Summary

We wish that we had a clear idea of how events would unfold in the next few months. Lacking that, we will rely on the lessons learned from history and past market turmoil. We were far more worried five years ago about COVID and lockdowns. Seventeen years ago, the financial crisis was just beginning to unfold, and that was a far more calamitous event. From those experiences, we remain committed to being disciplined allocators of capital. Holding steady in the face of rampant fear or greed is an important part of being a successful long‐term investor.

We will continue to be vigilant in managing risks and seeking opportunities based on your needs and goals. We appreciate your trust and confidence always, but particularly during trying times. Please let us know your thoughts, questions, and concerns.