No one knows if the events and market volatility of the early days of the Trump administration are predicting more of the same for the balance of the year. If they are, however, we all need to tighten our seatbelts as we are hard-pressed to remember a more dramatic month.

No one knows if the events and market volatility of the early days of the Trump administration are predicting more of the same for the balance of the year. If they are, however, we all need to tighten our seatbelts as we are hard-pressed to remember a more dramatic month.

A very strong year and post-election rally faltered in December. While investors awaited a Santa Claus rally (describing the tendency of equities to rally in the second half of the month), their hopes were dashed. Rising interest rates and profit-taking after a very strong 2024 led to losses in December. While weak breadth and a particularly poor last week of the year took some shine off markets, US investors had much to be grateful for in the equity markets. A look at the market and some of the headlines that impacted the market is always interesting.

2024 was the second consecutive year of 20%+ S&P 500 gains. That doesn’t happen very often, but it does help us forget the rotten year that 2022 represented and reinforces the importance of taking a patient, disciplined long-term approach to equity investing.

2024 was the second consecutive year of 20%+ S&P 500 gains. That doesn’t happen very often, but it does help us forget the rotten year that 2022 represented and reinforces the importance of taking a patient, disciplined long-term approach to equity investing.

Investors outside the US weren’t as happy, as weak economies, conflict, and leadership turmoil contributed to low single-digit returns. We have some additional thoughts about foreign markets later.

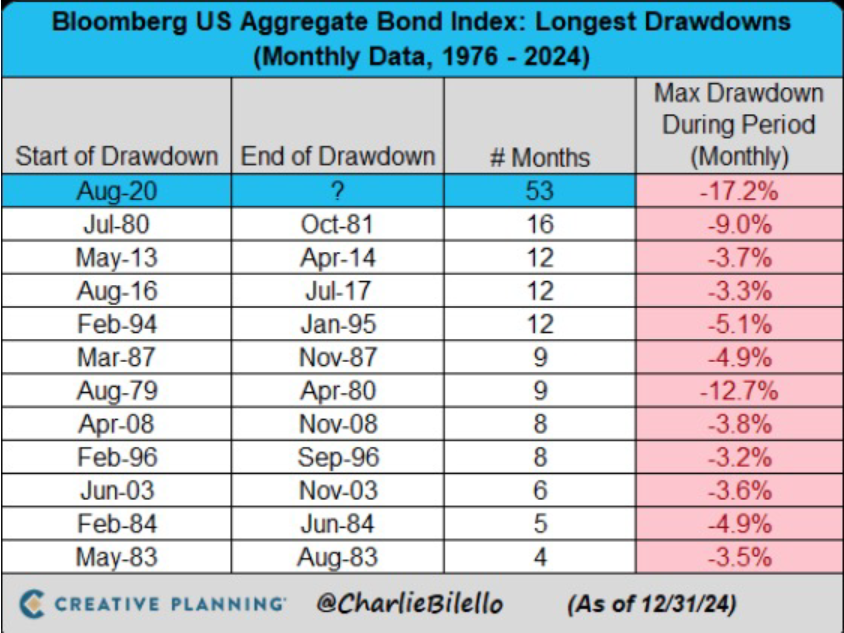

Bond investors also struggled. We have much to say about bonds in the pages that follow, but it is noteworthy to see how difficult a period it has been for the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index. Interest rates bottomed in the summer of 2020 (when we argued bonds were ‘expensive’), and since then, these “safe” holdings have generated meaningful losses. Bonds are more attractive today than they were in 2020, but we suggest that this cautionary tale, experienced in bonds over the last 4 years, can be a warning for investors in any expensively priced asset.

Bond investors also struggled. We have much to say about bonds in the pages that follow, but it is noteworthy to see how difficult a period it has been for the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Bond Index. Interest rates bottomed in the summer of 2020 (when we argued bonds were ‘expensive’), and since then, these “safe” holdings have generated meaningful losses. Bonds are more attractive today than they were in 2020, but we suggest that this cautionary tale, experienced in bonds over the last 4 years, can be a warning for investors in any expensively priced asset.

As we reflect on the year that ended and ponder what 2025 might hold, it is also interesting to peer back even further. Just five years ago, as 2019 drew to a close, western revelers didn’t pay much attention to a note from China regarding an outbreak of respiratory disease:

“the cause of the disease is not clear.” – China People’s Daily, 12/31/2019

Little did we know how COVID-19 would reorder the world. Fear, misery, illness, and death seemed everywhere. Even now, as we have added COVID-19 to the list of wintertime respiratory viruses to avoid or vaccinate against, the long shadow of the pandemic still lingers.

Some still suffer from symptoms of the disease in the form of “long Covid.” Governmental and institutional reactions to the pandemic, from lockdowns to suppression of discussion about the origins of the disease, have created an enormous crisis of confidence for public health officials, the medical establishment, and the media. In turn, the erosion of confidence and trust has had major political implications. In 2024, when 40% of people around the globe voted in national elections, every single incumbent received less support than in the prior election. This level of turnover in global leadership has never occurred on the scale that we are living through right now.

For the economy, lockdowns were devastating to many small businesses many of which were unable to compete with their larger breathen despite abundant government support. Workers acclimated to working at home and have been reluctant to return to the office. That has had huge negative impact on central business districts and businesses that relied on foot traffic. Educational losses were huge and will likely impact the capacity and readiness of a generation of students as they matriculate and become tomorrow’s workforce.

The response to the lockdowns, particularly in the US, was a surge of monetary and financial support not seen in scale since the Second World War. Pumping enormous stimulus into an economy in lockdown led to a surge in inflation that we continue to grapple with. A world awash in liquidity lifted asset prices in 2021, including the most speculative assets (think Gamestop and crypto stocks). Once monetary authorities began to raise interest rates, much of the damage was done. We have some additional thoughts about inflation below, but we don’t think the battle is over, and bond investors don’t seem to either.

That cheery trip down memory lane isn’t intended to depress. Instead, we think it is important to have some longer-term context for the key issues that the markets grappled with in 2024. How these issues play out in 2025 will determine market returns in the year ahead. Our thoughts and observations are detailed below.

Politics and Policy

As noted above, the world has seen unprecedented electoral turnover in the past year, punctuated by the US election in November that saw Donald Trump re-elected with a Republican majority (albeit tiny in the House) in Congress. It isn’t clear whether the US election was the driving force or simply a coincidental indicator, but dominoes continue to fall. The German government has collapsed and Justin Trudeau just resigned as Canadian Prime Minister. We think these developments portend a much more volatile 2025.

Ever since the 2008 Great Financial Crisis, governments and policymakers have taken a much more active role in the economy and markets. This was the inevitable outcome after the economy and markets were “saved” by extraordinary measures around the world. We have observed that the emergency response in 2008 and 2009 was appropriate, but maintaining a state of emergency for many years after the crisis had passed was a mistake. Voters seemed to agree in 2024, and many policies of the past four years appear to be in for sharp reversals.

Anger over immigration policy and the impact of inflation seemed to animate most voters last year. Domestically, promises of sharply reduced immigration (illegal and, perhaps, legal as well), imposition of tariffs on imported goods, and continued massive budget deficits don’t seem a recipe for lower inflation.

With Donald Trump, it isn’t clear what constitutes a rhetorical bomb or an actual policy objective. Since the inauguration, we have heard about annexing Canada, buying Greenland, and occupying the Panama Canal. Tariffs have been imposed and rescinded within hours. For our leaders, we don’t think impulsive actions are helpful, and we know that overreaction and impulsive moves are nearly always harmful for investors. Stay tuned but don’t panic!

Inflation and Interest Rates

While we could address inflation and interest rates separately, the two are too intimately tied together.

As we argued earlier, inflation wasn’t a problem until Covid and the lockdowns. In fact, in the years after the Great Financial Crisis, governments and central banks feared deflation. Interest rates were set at zero, and when that wasn’t enough to produce inflation, central banks embarked on quantitative easing (i.e., money printing). Despite their best efforts, inflation wouldn’t go above 2%. The Fed even announced that they were going to grade on a curve by using “average” inflation. That was quickly forgotten by the summer of 2022 when year-over-year inflation exceeded 9%.

Since then, the rate of inflation has come down. It is still above the Fed’s 2% target, but the annual rate of change has slowed. The problem for politicians is that a slowing growth rate isn’t the same as falling prices. Inflation is a tax on every single citizen. Some are hurt more than others, but it is hard to ask the man on the street if he can think of something that costs less than it did five years ago. Insurance, taxes, eggs, Netflix, etc. You name it, and there is a high chance it costs much more than it did.

Perhaps this is best summarized by a look at McDonalds (don’t tell RFK Jr.!). Because of its global footprint, many economists have used the price of a Big Mac to evaluate purchasing power parity between countries. That is an interesting exercise, but domestically, you can simply note that over the past five years, average prices have gone up 40% on the McDonald’s menu. Even if you don’t eat there, this is a tell about the impact of inflation that continues to be felt economy-wide.

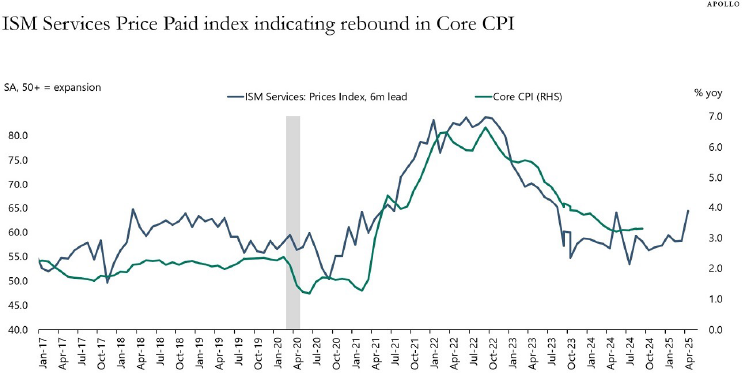

The Fed wasn’t thinking about this when they looked at the economic tea leaves in September and began to cut rates. They seemed to fixate on the trend in inflation as highlighted in a look at difference measures of core inflation. We don’t ascribe political intent to the timing of the 50 basis point rate cut but we do think it was odd for the Fed to move when inflation was still above their 2% target.

The Fed wasn’t thinking about this when they looked at the economic tea leaves in September and began to cut rates. They seemed to fixate on the trend in inflation as highlighted in a look at difference measures of core inflation. We don’t ascribe political intent to the timing of the 50 basis point rate cut but we do think it was odd for the Fed to move when inflation was still above their 2% target.

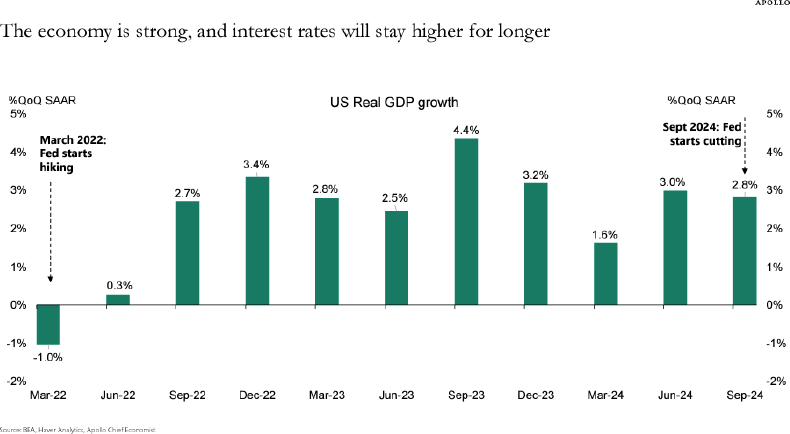

Declaring premature victory is always dangerous, but when we consider where the economy in all of its complex glory stood last fall, we remain perplexed by the Fed’s decision. One might think that if quarterly GDP was negative, you wouldn’t be raising rates. It is also reasonable to be surprised by the launching of an easing cycle with GDP growth at 2.8%.

Declaring premature victory is always dangerous, but when we consider where the economy in all of its complex glory stood last fall, we remain perplexed by the Fed’s decision. One might think that if quarterly GDP was negative, you wouldn’t be raising rates. It is also reasonable to be surprised by the launching of an easing cycle with GDP growth at 2.8%.

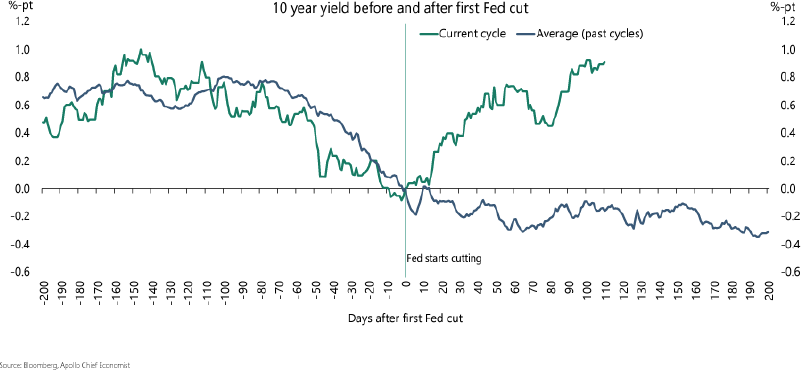

Bond investors seem to share our confusion. Since the Fed began cutting in September, the short rates they control have come down by 1%, but the long rates set in the market have risen by ½% That isn’t how this is supposed to work:

Bond investors seem to share our confusion. Since the Fed began cutting in September, the short rates they control have come down by 1%, but the long rates set in the market have risen by ½% That isn’t how this is supposed to work:

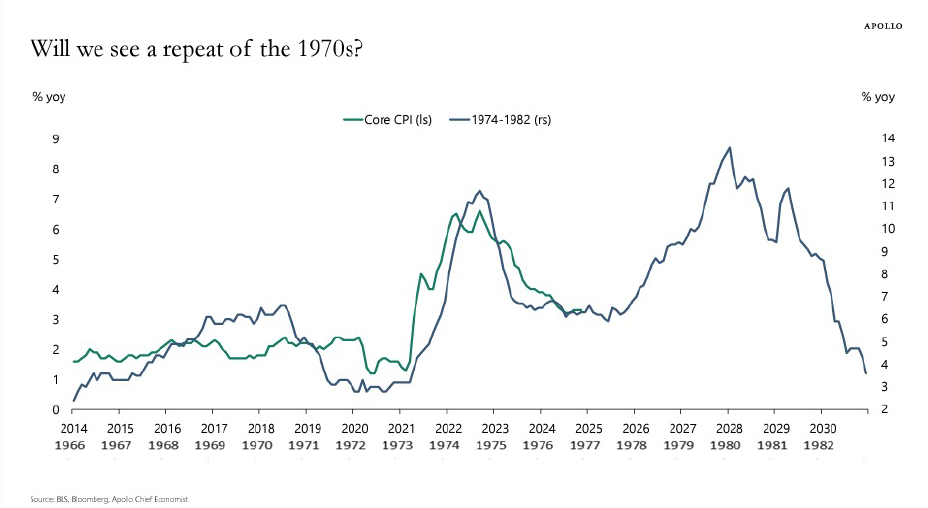

Students of history and experienced investors may be having nightmares about that 70’s show. We aren’t referring to a bad sitcom. Instead, we look at the parallels to the 1970s fight against inflation.

Students of history and experienced investors may be having nightmares about that 70’s show. We aren’t referring to a bad sitcom. Instead, we look at the parallels to the 1970s fight against inflation.

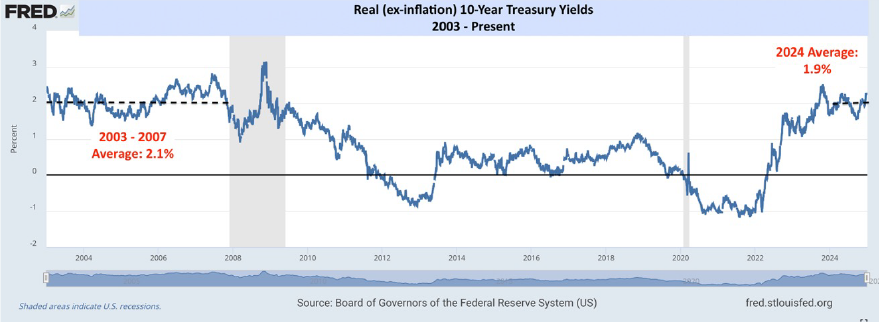

There may be a more charitable explanation for the rise in rates. Interest rates are a combination of inflation expectations (because you want to maintain purchasing power) and real rates. Real rates are the returns an investor receives over and above their expectation (right or wrong) about inflation. Using current embedded market expectations for inflation accounts for 22 basis points (i.e., .22%) of the 1/2% increase in Treasury rates since September. The balance is a jump in real rates. This increase, however, may simply be returning us to “normal:”

There may be a more charitable explanation for the rise in rates. Interest rates are a combination of inflation expectations (because you want to maintain purchasing power) and real rates. Real rates are the returns an investor receives over and above their expectation (right or wrong) about inflation. Using current embedded market expectations for inflation accounts for 22 basis points (i.e., .22%) of the 1/2% increase in Treasury rates since September. The balance is a jump in real rates. This increase, however, may simply be returning us to “normal:”

Prior to the GFC, real rates averaged 2.1%, and we are just getting back to that level now. So much that has happened since the GFC was abnormal that we may not have a solid grasp of what is normal.

Regardless of the reason for the increase in rates, we would make some observations:

- Ten-year Treasury yields near 5% aren’t a problem for the economy. We have been here before, and it is the transition from low to higher rates that is a challenge, not the ultimate destination.

- Money market yields in the 4% range aren’t a problem.

- Higher yields do not support silly equity valuations. In 2021, when interest rates were zero, every asset went up. Good, profitable companies were more valuable. Worthless, profitless, speculative companies were even more valuable. When lottery tickets are free, why not play? Now, with interest rates higher (closer to “normal?), we think valuation will once again be a consideration for investors.

- Finally, at risk of being made fools in the future, we will state firmly that the zero interest rate era is over, and it isn’t coming back.

Will the US continue to dominate world equity performance?

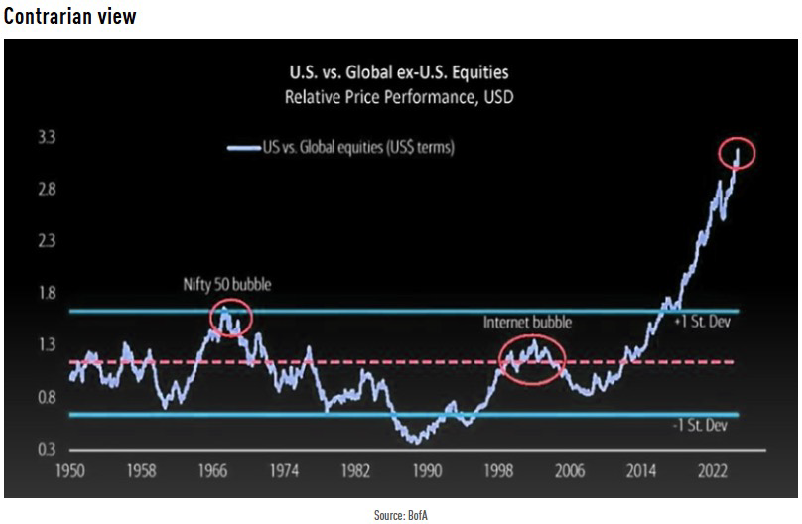

As noted earlier, the US market was the standout among world markets in 2024. This, however, isn’t new. Modest outperformance in 2023 didn’t make a dent in the historically unprecedented outperformance of the US versus the rest of the world.

As noted earlier, the US market was the standout among world markets in 2024. This, however, isn’t new. Modest outperformance in 2023 didn’t make a dent in the historically unprecedented outperformance of the US versus the rest of the world.

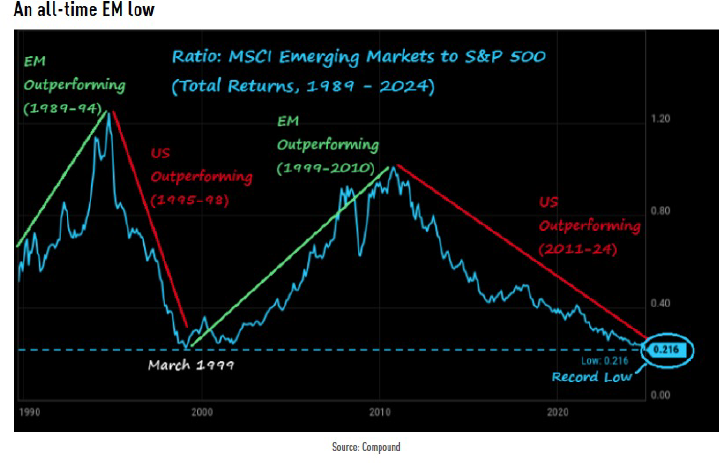

For the longest time, investors were also told that emerging markets had to be a portfolio building block. Younger demographics, globalization of trade, growing middle class consumer appetites and and appealing valuations demanded exposure, particularly to China. It hasn’t worked out very well.

For the longest time, investors were also told that emerging markets had to be a portfolio building block. Younger demographics, globalization of trade, growing middle class consumer appetites and and appealing valuations demanded exposure, particularly to China. It hasn’t worked out very well.

What explains these results? Policy differences, leadership, rule of law and custom are all important. More basically, the US has been a hotbed of innovation, and technol0gy has been the leading sector for many years. Tech stocks make up a much larger percentage of the US market than in foreign or emerging markets. Whatever the combination of factors, the question is what has been priced in?

US exceptionalism seems fully priced. Can things get better? Perhaps. Could something derail US progress? Of course. Are foreign assets objectively cheaper than their US counterparts? Absolutely. But until something catalyzes a change, it is difficult to advocate heavy foreign exposure for a US investor. Europe’s newfound commitment to self defense and Germany’s pending fiscal stimulus may serve as the drivers of change. We are confident that if the tide turns, it will play out not over months but over years, and we will have time to adjust.

Will the US markets broaden out or remain a Magnificent Seven Story in 2025?

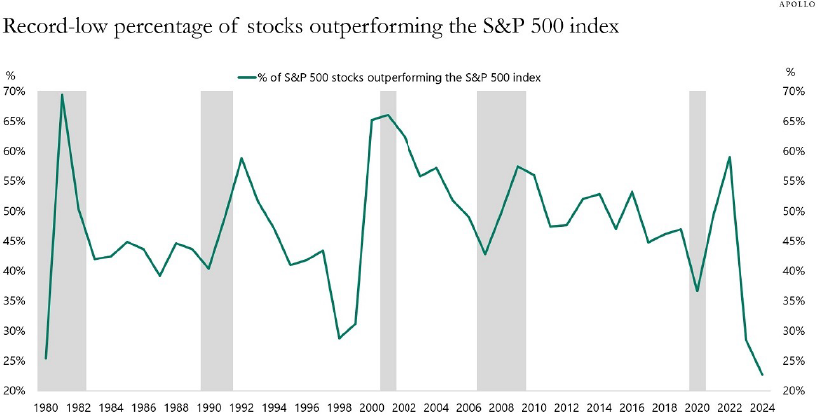

A long-held view by professional investors is that a healthy market is one where most stocks are participating in an upside move. This is described as market breadth, and markets where a few stocks lead the way while the average stock struggles aren’t regarded as sustainable. Like many long-held views, the past couple of years have seemed to turn this wisdom on its head.

A long-held view by professional investors is that a healthy market is one where most stocks are participating in an upside move. This is described as market breadth, and markets where a few stocks lead the way while the average stock struggles aren’t regarded as sustainable. Like many long-held views, the past couple of years have seemed to turn this wisdom on its head.

In 2024, the average stock was up but couldn’t keep pace with the mega-cap tech stocks:

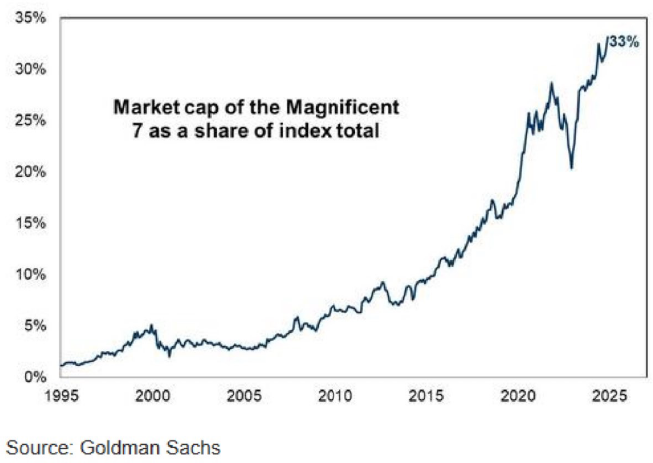

The “Magnificent Seven” is the short-hand description of the basket of mega capitalization growth stocks that now dominate the US and Global Markets. Apple, Amazon, Alphabet (i.e., Google), Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla make us this illustrious group. When an investor invests $1 in an S&P 500 Index Fund, 34 cents of that dollar are divided among those seven names:

The “Magnificent Seven” is the short-hand description of the basket of mega capitalization growth stocks that now dominate the US and Global Markets. Apple, Amazon, Alphabet (i.e., Google), Meta (Facebook), Microsoft, Nvidia, and Tesla make us this illustrious group. When an investor invests $1 in an S&P 500 Index Fund, 34 cents of that dollar are divided among those seven names:

This concentration has drawn comparisons to the dot-com bubble that burst in 2000. It is different in the sense that these market leaders are great companies with terrific balance sheets. More importantly, they are very profitable and earnings continue to grow for all of them.

This concentration has drawn comparisons to the dot-com bubble that burst in 2000. It is different in the sense that these market leaders are great companies with terrific balance sheets. More importantly, they are very profitable and earnings continue to grow for all of them.

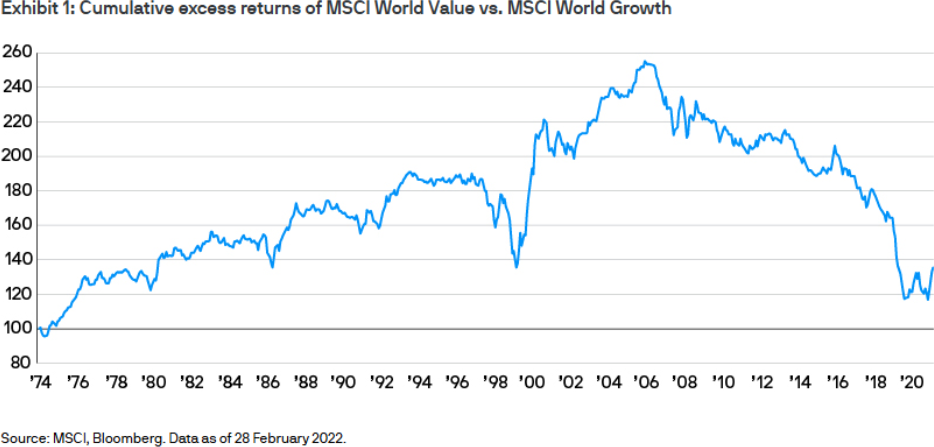

With these concentration extremes, the corollary is that traditional value stocks are comparatively cheap.

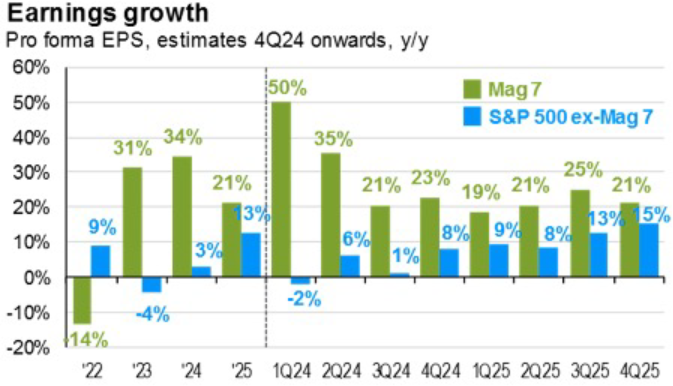

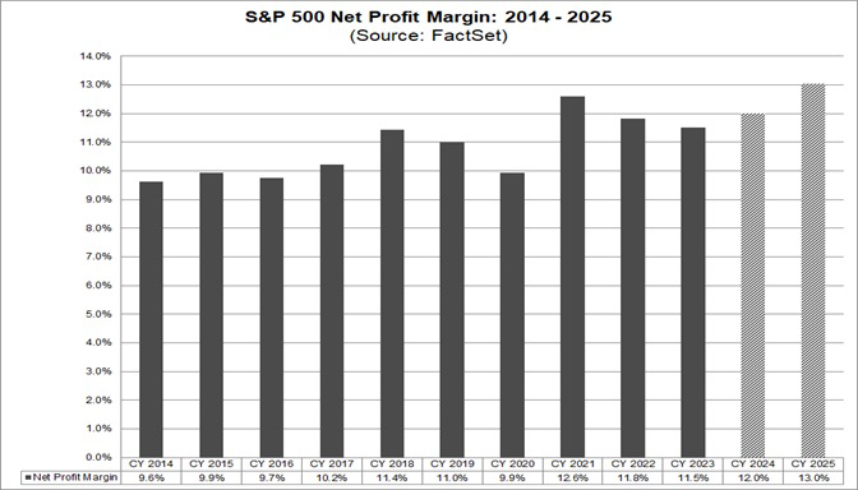

Ardent bulls, with momentum on their side, shrug off valuation and concentration concerns and focus instead on profitability:

Ardent bulls, with momentum on their side, shrug off valuation and concentration concerns and focus instead on profitability:

US equity profit margins have reached highs that no one thought possible. If margins are up 30% in ten years, multiples should also rise. If a given asset can produce more money, it is worth more, or so the argument goes. We don’t disagree, but we might quibble about how much more to pay.

When we think about the US market, the increase in interest rates strikes us as more of a potential catalyst for a broadening of leadership. We saw that unfold in 2022 as the Fed embarked on their tightening campaign to combat inflation. If they are closer to the end than the beginning of this rate-cut cycle, value may become more relevant for investors.

Can an expensive US stock market get more expensive?

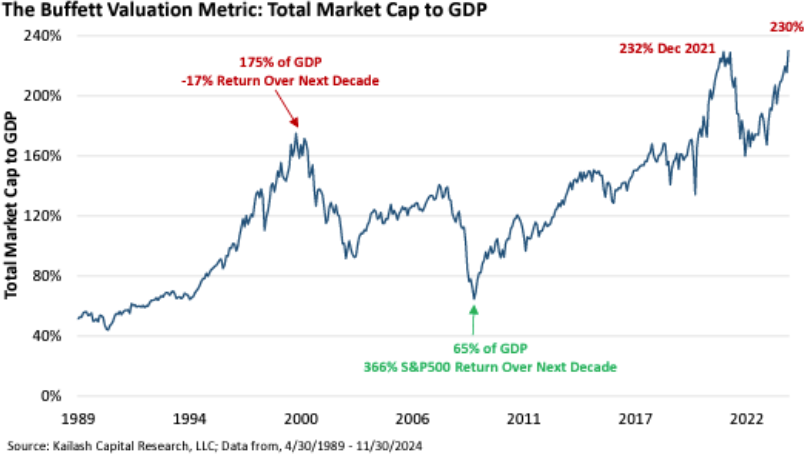

No commentary of ours would be complete without hand-wringing over equity valuations. The Magnificent Seven might continue to work higher, or the market might broaden. The US economy could be turbocharged by tax cuts and a lower regulatory burden by the new Trump administration. No matter how those issues play out, we must never lose sight of the basic math of high valuations. Buying something at a high price makes it less likely to produce attractive, forward returns. Buying an asset cheaply enhances the chance of a happy ending. Consider the oft-cited Buffet indicator, comparing equity valuations to GDP

No commentary of ours would be complete without hand-wringing over equity valuations. The Magnificent Seven might continue to work higher, or the market might broaden. The US economy could be turbocharged by tax cuts and a lower regulatory burden by the new Trump administration. No matter how those issues play out, we must never lose sight of the basic math of high valuations. Buying something at a high price makes it less likely to produce attractive, forward returns. Buying an asset cheaply enhances the chance of a happy ending. Consider the oft-cited Buffet indicator, comparing equity valuations to GDP

Summary

We are grateful for your trust and confidence. We don’t know what the balance of 2025 will hold, but it seems likely that the stage is set for greater volatility in the markets. Torsten Slok, chief economist for Apollo, compiled a list of risks that he sees in 2025.

We are grateful for your trust and confidence. We don’t know what the balance of 2025 will hold, but it seems likely that the stage is set for greater volatility in the markets. Torsten Slok, chief economist for Apollo, compiled a list of risks that he sees in 2025.

We might assign different probabilities to these perils, but it seems a reasonable list of worries to keep us up at night. While we note these concerns, we need to acknowledge that as the new year begins, the economy is growing, and unemployment is low. That is not a bad place to start the year.