Although the calendar tells us it is autumn, in Denver, it feels like summer. So far in October, we have had multiple record-high temperatures, including readings of 90 degrees. October 7 is the average first freeze on the front range, but today’s high will be 80 degrees.

A similar observation could be made about the financial markets. Equities avoided the summer doldrums and continued to rally. A nearly 2% gain in September was the US market’s fifth consecutive monthly gain. This is the 30th time since 1950 that the market has had a five-month winning streak, and returns are positive in the ensuing 1, 3, 6, and 12 months. History doesn’t guarantee a similar result, but with monetary winds changing in September, central bankers around the world are doing what they can to extend the economic expansion and avoid the pain of a recession.

Revisiting Our Worries

When the Schaefer kids were young, a family friend and long-time pediatrician was a source of great comfort. Dr. Jim would attend to the usual bumps, bruises, sniffles, and stomach bugs. But his best advice had to do with the scary things the kids worried about beneath the bed. When my youngest described what frightened him, Dr. Jim never missed a beat. He pulled out his pad and quickly wrote a prescription for “Scary Spray.” He explained that it was a liquid dispensed in a spray bottle. We could fill the order at our neighborhood pharmacy. With the spray bottle in hand, anytime something scary seemed near, Dr. Jim recommended two squirts from the bottle in the direction of the fearsome foe.

The pharmacist at King Soopers smiled when the script was presented but dutifully returned with a very official-looking bottle, complete with a pharmacy label and instructions. We took the Scary Spray home, and it worked like a charm. With one or two spritzes from the bottle, the monsters under the bed and in the closet were kept at bay.

I recalled that quick remedy for lingering fears as we reflected on the worries we noted in our mid-year report. Unfortunately, for grown-ups and investors, we have yet to find an effective “Scary Spray.” In our experience, talking openly about what worries exist and what might go well is the best therapy. We were worried by many things in July, but our concerns really boiled down to five key areas:

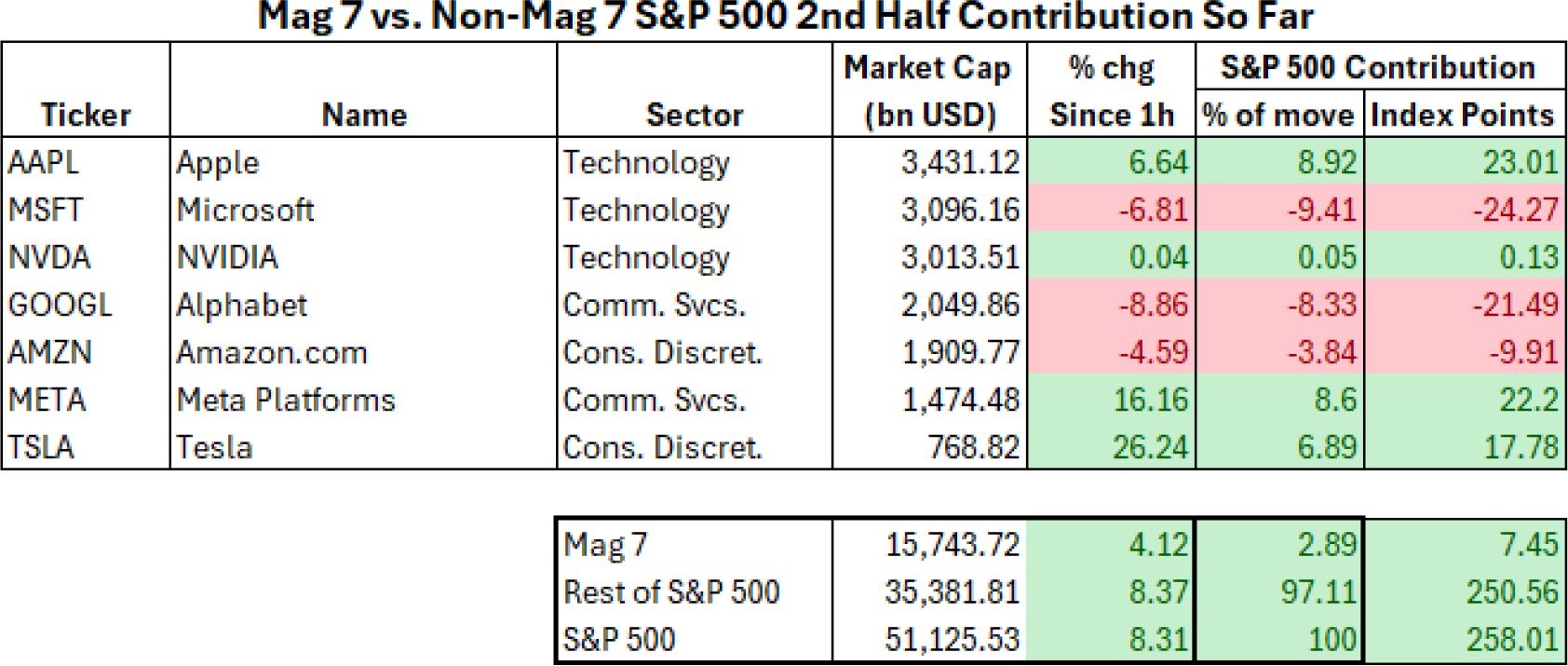

Through the first half of the year, the tech giants collectively dubbed the “Magnificient Seven” dominated market performance. In the capitalization-weighted indexes that most investors pay attention to, larger names disproportionately impact index performance. The seven tech giants were trouncing all of the other publicly traded companies (i.e., the meek 493), and if an investor didn’t own those stocks, there was little hope of keeping pace with the market.

Generally, healthy market advances are characterized by broad participation, meaning most stocks are rising. Narrow advances, like the market led by the Magnificent Seven, often precede market pullbacks. This was a significant worry for us at mid year, but we are pleased to report that the problem has begun to correct. The tech giants have stalled out in recent months, and during the third quarter, those names accounted for just 3% of the market’s gain. The other 493 S&P 500 stocks did the heavy lifting and provided the other 97% of the gain.

Generally, healthy market advances are characterized by broad participation, meaning most stocks are rising. Narrow advances, like the market led by the Magnificent Seven, often precede market pullbacks. This was a significant worry for us at mid year, but we are pleased to report that the problem has begun to correct. The tech giants have stalled out in recent months, and during the third quarter, those names accounted for just 3% of the market’s gain. The other 493 S&P 500 stocks did the heavy lifting and provided the other 97% of the gain.

This change was seen in many areas. Early in July, small-cap stocks surged. While their performance cooled, more interest rate-sensitive sectors raced ahead, with utilities and real estate stocks performing particularly well. It isn’t often that utilities are the best-performing sector unless the market is retreating.

We view this broader participation as good news. While it doesn’t guarantee positive returns on a go-forward basis, it does reflect a more resilient economy and a healthier market. The market remains top-heavy, but we feel much better about this persistent worry from the past few years.

Our second concern had to do with interest rates. The Fed and the market have seemed at odds in the past two years with regard to the direction and speed of interest rate changes. Investors had priced in larger rate cuts, beginning sooner and lasting longer than any member of the Federal Reserve. That seemed to us to be a recipe for unhappiness, particularly as the economy remained strong. Early in the summer, economic data began to weaken, and it seemed that a stronger case could be made for rate cuts.

By the time Labor Day arrived, the question was not if the Fed would cut but by how much. Despite a rebound in economic activity (GDP for the third quarter up 3%) and continued low unemployment, the Fed decided they were behind, and rates should be 50 basis points (.5%) lower. Markets were thrilled that an easing cycle had begun, and equity investors were licking their chops at the prospect of an additional 200 basis points of cuts.

We aren’t sure that any more cuts are actually justified. On October 4, the US had a blowout jobs report with 245,000 new jobs being created. As with all economic data points, this one is likely to be revised, but it isn’t a report that can be used to make the case that the job market is collapsing. Cutting interest rates into a growing economy with low unemployment doesn’t seem like sound policy. We worry that the Fed and other central banks risk restarting an inflation problem. Count us as still worried about this issue.

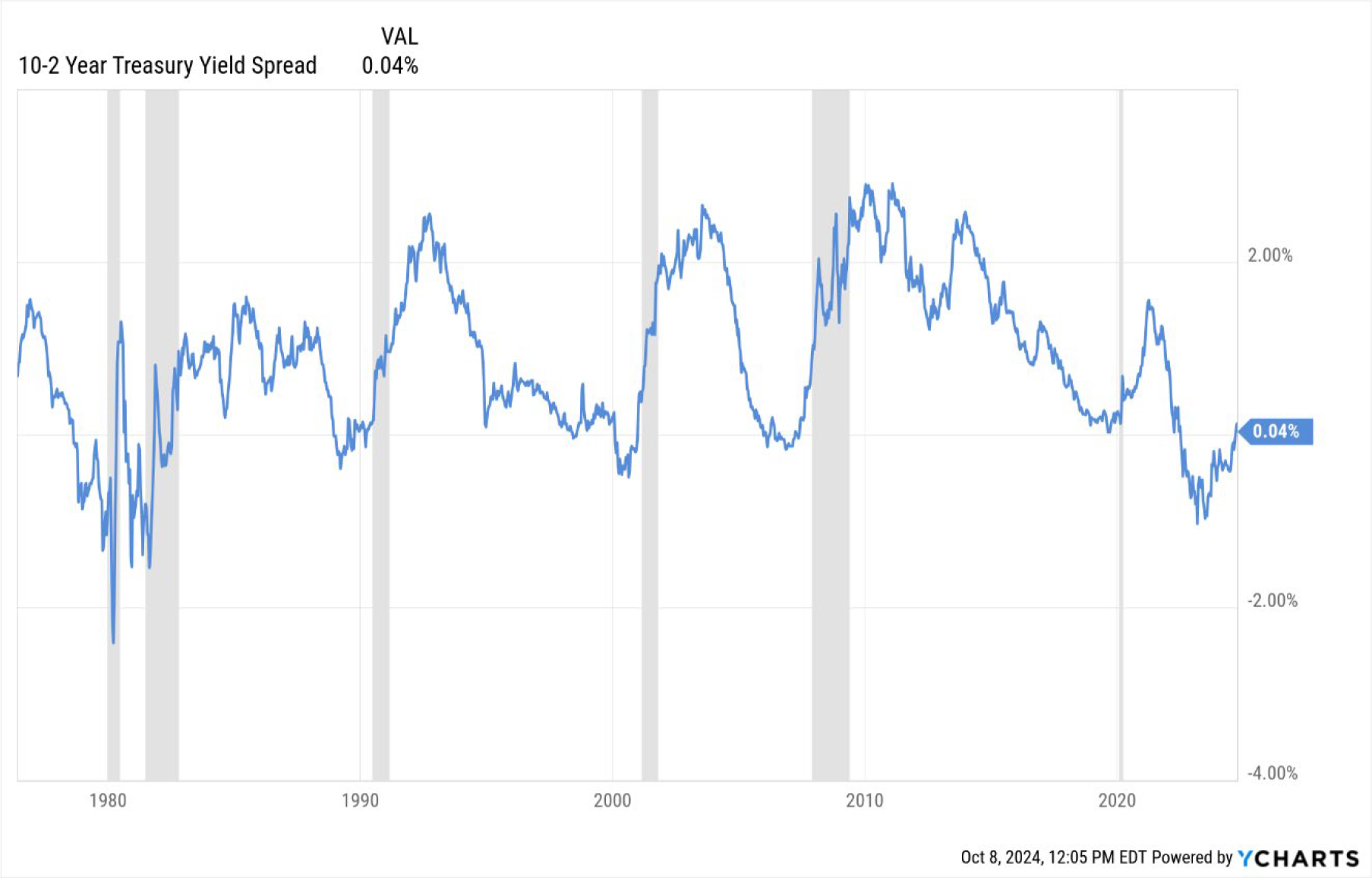

Interestingly, the reaction in the bond market seems to reflect this concern. While short-term rates have come down since the Fed announcement, longer-term rates including the all important 10 year Treasury have actually gone up. As of this writing, the 10 year yield is now back above 4%. This, it seems to us, reflects the worry in the bond market that stimulus today will accelerate inflation tomorrow.

Interestingly, the reaction in the bond market seems to reflect this concern. While short-term rates have come down since the Fed announcement, longer-term rates including the all important 10 year Treasury have actually gone up. As of this writing, the 10 year yield is now back above 4%. This, it seems to us, reflects the worry in the bond market that stimulus today will accelerate inflation tomorrow.

As important as the actual level of rates is, the spread between various maturities is even more important. Historically, the difference between 10-year and 2-year Treasuries was a terrific forecasting tool. When the normally upward-sloping curve (i.e., longer-term yields higher than shorter-term yields) is inverted, that forecasts a recession. Once the Fed began cutting rates, the curve would “un-invert”. While we moved in that direction, the move has been driven more by longer rates rising. This seems to us a logical expression of concern about whether we have really solved the inflation problem.

To that end, our third worry is one that hasn’t disappeared. The scandalous budget situation in the United States gets worse with each passing month. September 30 was the end of the fiscal year, and a country not at war has run a $2 trillion deficit. And in the heat of an election cycle, the issue doesn’t even merit a mention from either Presidential candidate. In terms of the deficit, the election seems to be a contest between bad and worse.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, a nonpartisan group that advocates for lower deficits, suggests that Trump’s proposals would add $7.5 trillion to the deficit over the next decade while Harris’s policies would add $3.5 trillion. These amounts are over and above the $22 trillion of anticipated deficits in the baseline scenario. The magnitude of this deficit spending is so great that this alone makes it very unlikely that we will experience tame inflation in the years to come.

Interest on the debt now exceeds all of our spending on defense. Historian Niall Ferguson has noted that empires in that condition don’t remain empires for very long. In the same way that high market valuations don’t cause bear markets, we don’t think high deficits will cause a recession, but they will continue to erode market price signals and limit the ability of the country to respond to a real crisis when one appears. On this matter, we are discouraged enough that we would be inclined to drink Scary Spray if we can find any.

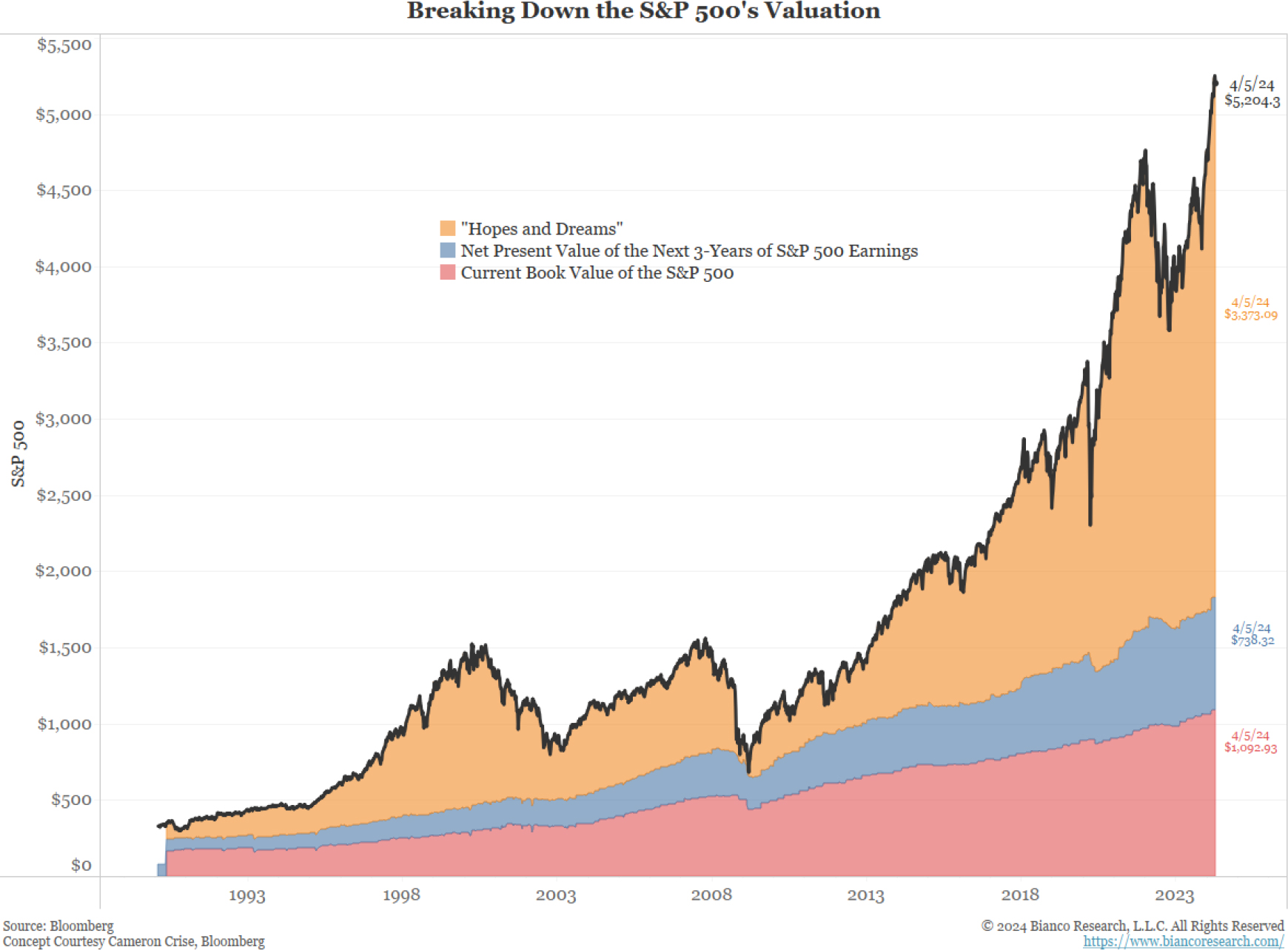

Like a monster beneath the bed, our fourth great fear regards equity valuations. We know we sound like a broken record on the topic, but we will stop mentioning the issue when valuations improve. We can describe an expensive market in many ways, but two of our favorites are noted below. The first is a chart examining the “Hopes and Dreams” component of stock prices. Equity investors are, by nature, forward-looking and somewhat optimistic, but today’s numbers suggest that optimism may have overtaken reason.

Like a monster beneath the bed, our fourth great fear regards equity valuations. We know we sound like a broken record on the topic, but we will stop mentioning the issue when valuations improve. We can describe an expensive market in many ways, but two of our favorites are noted below. The first is a chart examining the “Hopes and Dreams” component of stock prices. Equity investors are, by nature, forward-looking and somewhat optimistic, but today’s numbers suggest that optimism may have overtaken reason.

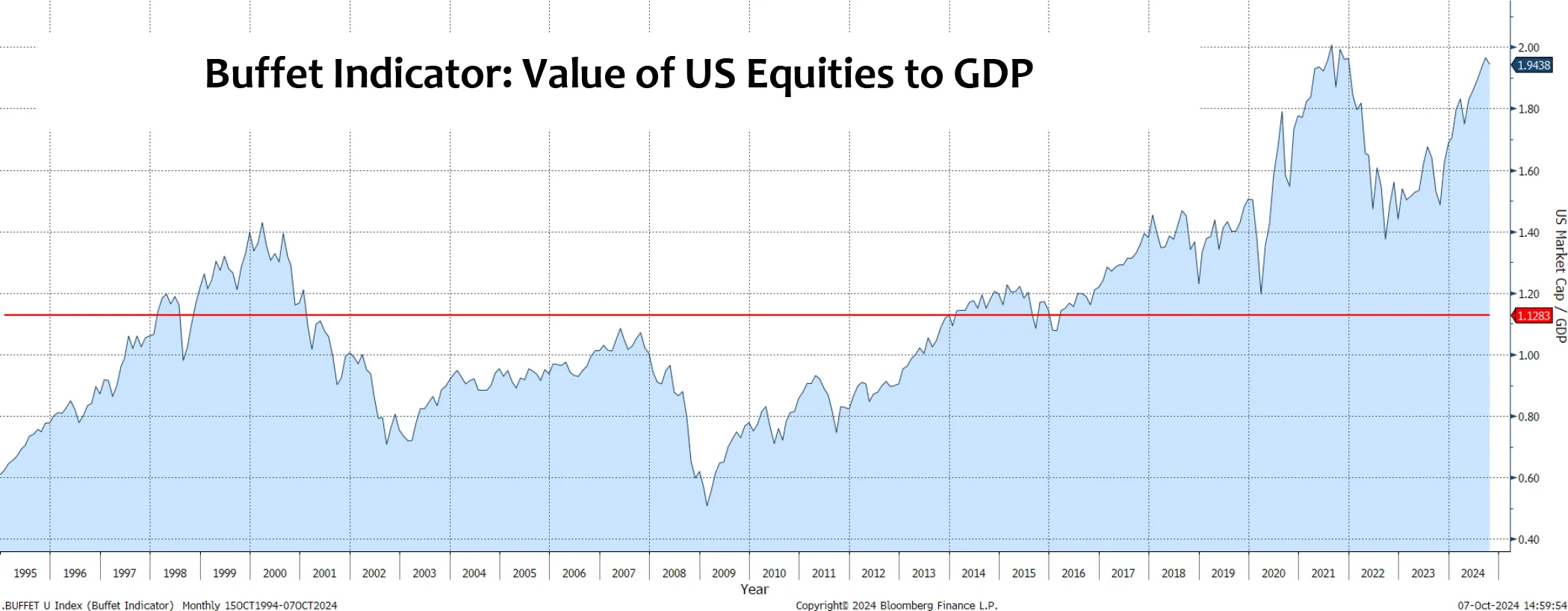

The second valuation chart is one of Warren Buffet’s favorites. It compares the total value of US equities to US GDP. Although current results are below the November 2021 high of more than 200% of GDP, we are rapidly approaching that level. Expensive assets can get more expensive, but high valuations should be respected.

Our final worry in July was political turmoil. When we made our observations in July, Joe Biden was the Democratic nominee despite his debate performance. In less than three months, Joe Biden ceased to be the nominee of his party and was replaced on the ticket, but not in the oval office, by Kamala Harris without a single vote being cast. As this unfolded, Donald Trump was the target of two would-be assassins. This is starting to make 1968 seem tame.

When we wrote in July about our worries, we were focused on the fact that 40% of the globe was electing new leaders in 2024. While the prospect of confusion and contention in the US is a major worry, our focus is shifting toward the unfolding chaos around the world. As the world marks the anniversary of the terror attacks in Israel, the Middle East is at war. How far it spreads will profoundly impact the region and the global economy, but the US seems distracted and unable or unwilling to exert its leadership or will. Meanwhile, in Europe, the war in Ukraine grinds along in its third year with little sign of an end. The cost in blood and treasure is appalling. Despite the aggressive counter-attack into Russian territory by Ukrainian forces this summer, Russia seems to be gaining the upper hand. With winter looming, it is fair to ask how long this stalemate can continue.

The world is a far scarier place when the global policeman for the last eighty years is absent.

What, me worry?

Lest we be accused of being too cynical or pessimistic, we harken back to Alfred E. Neuman and Mad Magazine. Only after the Three Mile Island meltdown did Alfred begin to worry, but that was short-lived. In that spirit, we must acknowledge the many reasons to be optimistic as we enter the fourth quarter.

The simplest and most important is that we are in a bull market. Returns for both stocks and bonds have been tremendous over the past year. Bull markets in any asset tend to be self-reinforcing until something changes the trend. While any of our worries could derail the outlook, right now, markets are climbing the wall of worry, and it is important to enjoy the ride.

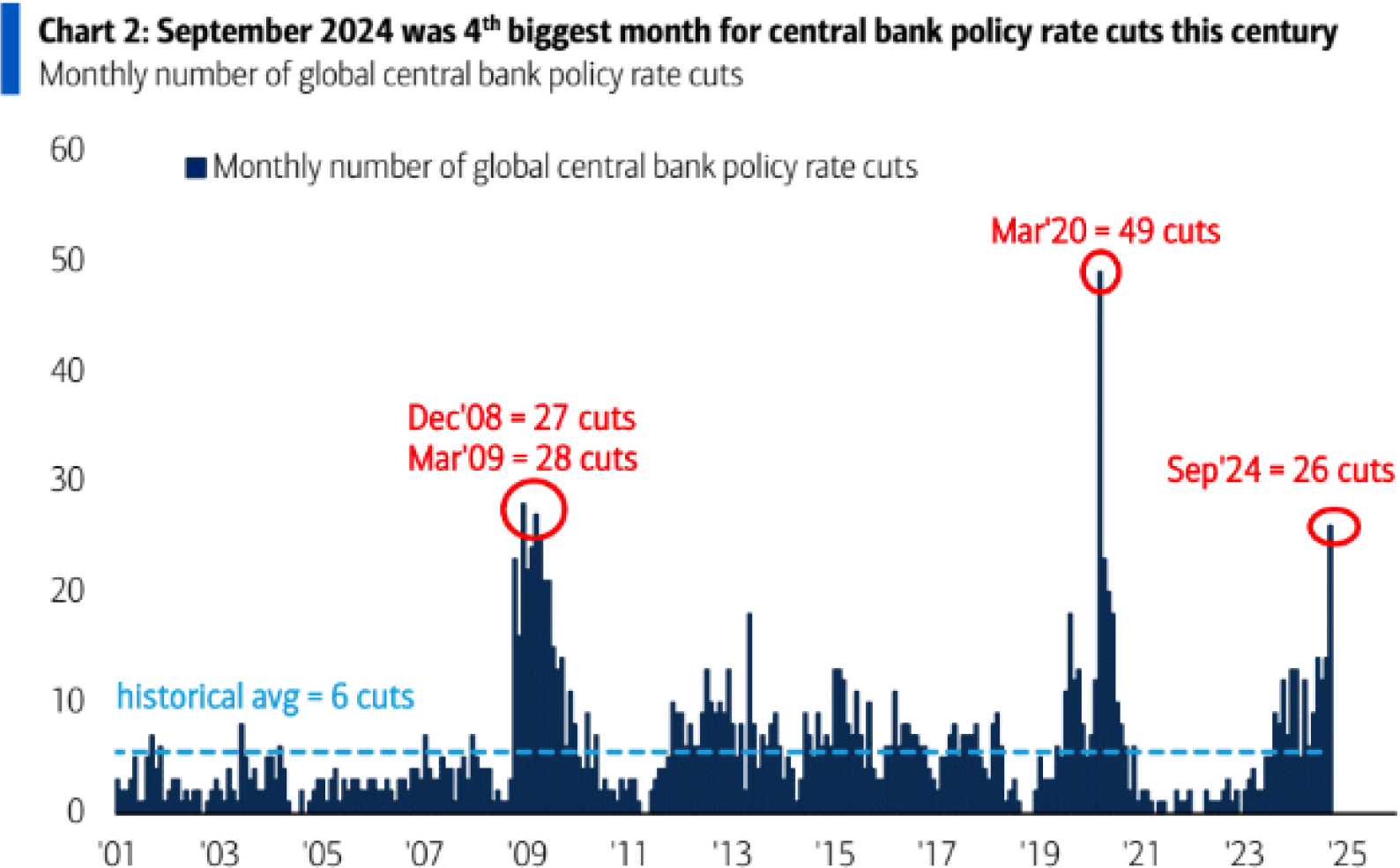

With the Federal Reserve interest rate cut last month, followed closely by aggressive stimulus measures out of China, September became the fourth biggest month of global central bank cuts this century. As highlighted below, the only months with more cuts were in the depths of the Great Financial Crisis and during the unfolding of the Covid pandemic.

We find it hard to draw many parallels between economic conditions in 2008 and 2020 and current conditions. What can’t be argued, however, is that aggressive rate cuts are supportive of economic activity and asset prices. The old adage that a wise investor doesn’t “fight the Fed” seems particularly apt today.

We find it hard to draw many parallels between economic conditions in 2008 and 2020 and current conditions. What can’t be argued, however, is that aggressive rate cuts are supportive of economic activity and asset prices. The old adage that a wise investor doesn’t “fight the Fed” seems particularly apt today.

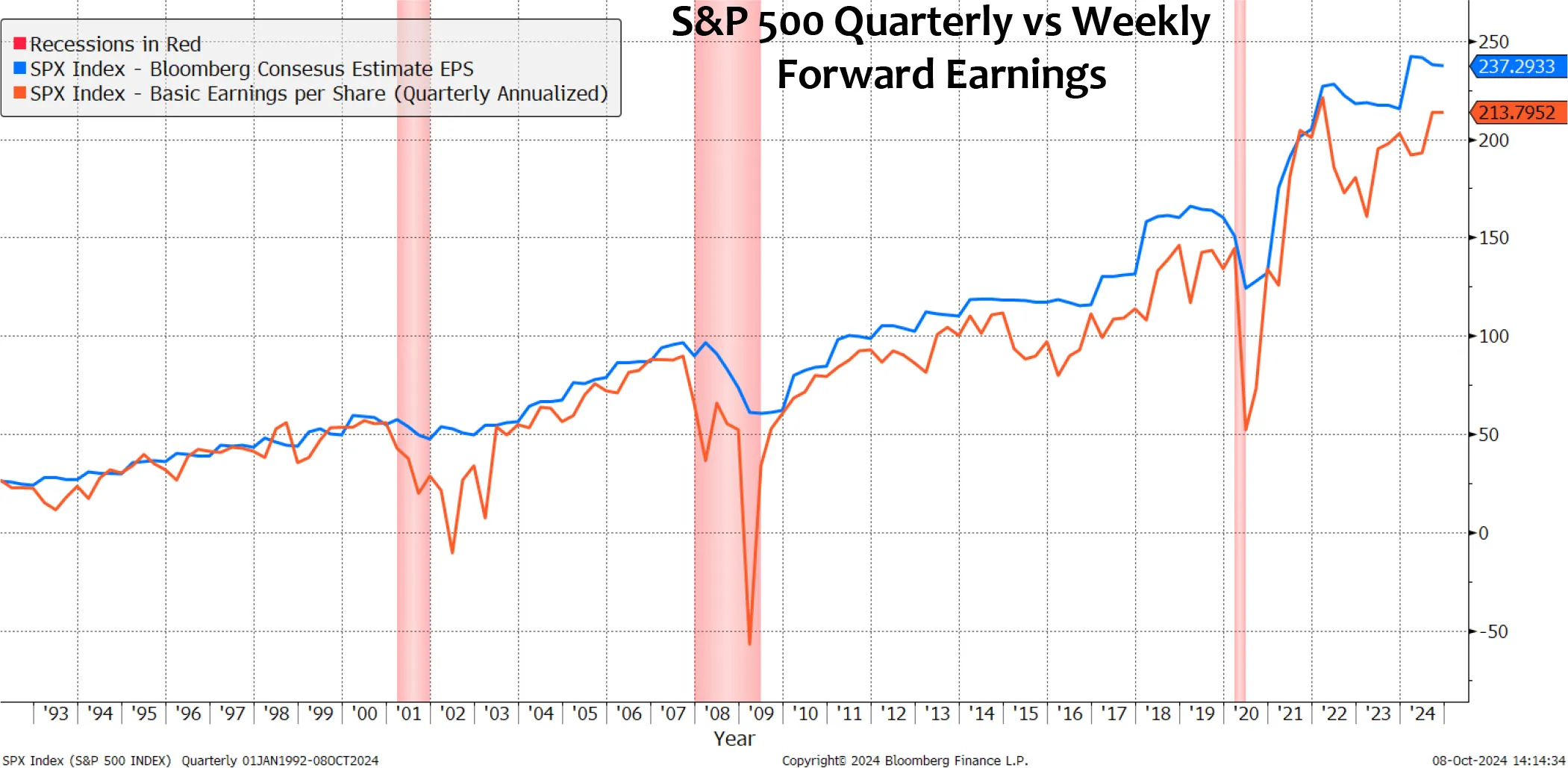

Just as critically, stock prices will ultimately follow corporate earnings. Reasonable investors can differ about what price to pay for $1 of earnings, but if earnings are rising, equity prices are likely to follow. As is highlighted below, forward earnings estimates have led actual earnings higher and continue to suggest strength in the coming quarters. Against this backdrop, it is difficult to be too bearish.

Summary

As we look toward year-end, we want to give you a balanced view of the risks and opportunities we see today. We view ongoing risk management as the critical component of our work. Robert Rubin, the former head of Citibank and Treasury Secretary during the Clinton administration, had a brief but useful summary of how he thought about risk:

“As I think back over the years, I have been guided by four principles for decision making. First, the only certainty is that there is no certainty. Second, every decision, as a consequence, is a matter of weighing probabilities. Third, despite uncertainty, we must decide and we must act. And lastly, we need to judge decisions not only on the results, but on how they were made.”

We look forward to your thoughts, questions, and comments. As we move toward year-end, tax and investment housekeeping are at the top of our minds, but please let us know if you have any time-sensitive matters that we need to discuss.