If the first quarter of 2023 proved anything, it is just how unpredictable the world is. After a painful year for the financial markets in 2022, with stubborn high inflation pushing up interest rates and punishing speculative investments and conservative bonds, the script was completely flipped in the first quarter.

If the first quarter of 2023 proved anything, it is just how unpredictable the world is. After a painful year for the financial markets in 2022, with stubborn high inflation pushing up interest rates and punishing speculative investments and conservative bonds, the script was completely flipped in the first quarter.

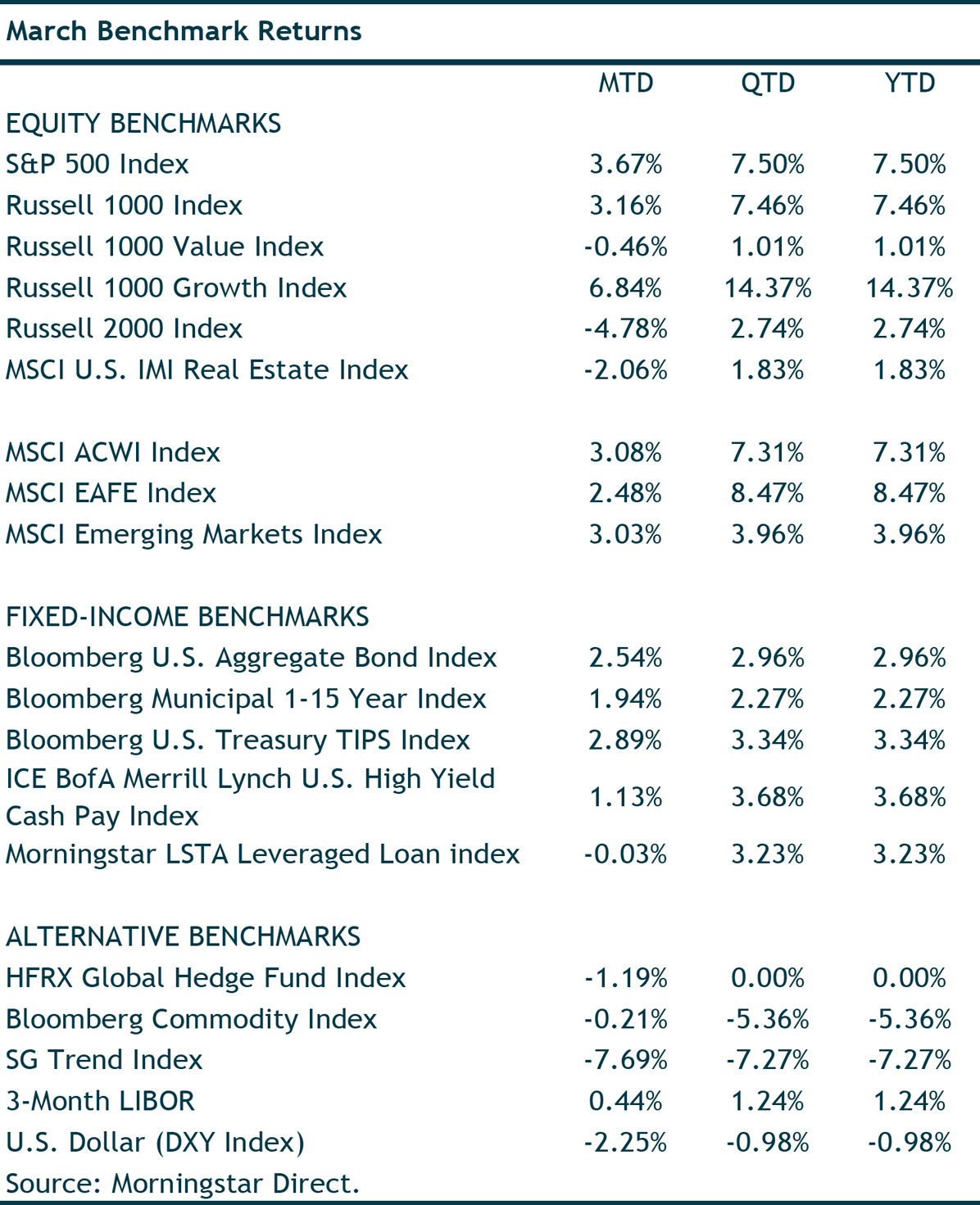

Evidence that inflation was coming down (albeit still at levels too high for the Fed), led to lower interest rates and a rally in bonds. Growth stocks rallied while last year’s winners (value stocks) underperformed. The meek seemed to inherit the earth.

This pattern accelerated in March with the banking crisis. If there was a consensus view at the beginning of the year, it was that the US bank system was strong and secure. That faith was tested when two large regional banks were shuttered, followed by one of the world’s globally systemically important banks, Credit Suisse, being acquired by a competitor.

We have some additional thoughts and comments on the banking issues below, but these very unexpected developments drove interest rates down. And like Pavlov’s dog, investors concluded that the largest cap stocks (FAANGs or MAGMA depending on your preference for an acronym) were the place to hide. As we write this in early April, 8 stocks have accounted for approximately 150% of the S&P 500 year to date gain. This underlying weakness for the remaining 492 stocks isn’t a bullish sign.

The Banking Crisis

By now you have probably read more than you ever hoped to about the March bank run that culminated in in the closer of Silicon Valley Bank in California and Signature Bank in New York. For many people with memories of the Great Financial Crisis, a March financial implosion was too similar to the March 2008 collapse of Bear Stearns. We don’t think last month’s events are the start of a replay of the 2008 crisis, but there is nothing good about the crisis and there is ample blame to share. This was fundamentally a liquidity crisis. Every bank faces a liquidity crisis every day. The fact is that when you deposit funds in the bank and expect to be able to withdraw them on demand, the potential exists for your needs to be ill timed if the bank has made a loan or (in the case of Silicon Valley Bank) bought longer term government securities that can’t be readily converted to cash. This mismatch of assets and liabilities for a bank has always and everywhere created the potential for a bank run. Since the 1930s, a combination of deposit insurance (so depositors don’t feel like they need to be the first to panic), heavier regulation and liquidity provision by the Federal Reserve (as the “lender of last resort”) has been used to maintain confidence and to prevent the type of wholesale bank runs that crippled the US economy in the 1930s. We expect that these tools will again be employed in service of this objective.

In 2008, bank runs occurred less due to liquidity issues and more due to solvency issues (i.e., banks had made bad loans, and many were bankrupt as the loans would never be repaid). Because depositors didn’t want to wait to learn where their banks stood, deposit insurance was extended to all bank deposits for a year. This effectively cauterized the bank run, but the price was high for financial institutions. The Dodd Frank legislation dramatically changed the regulatory landscape for banks of all sizes. While it probably made the entire industry more secure, it has had the unintended consequence of creating two tiers of banks. The first are the big four (JP Morgan, Citibank, Wells Fargo and Bank of America). These four are widely understood to be “too big to fail” so depositors trust that if their institution gets in trouble, the Fed and Treasury will ultimately guarantee all deposits. The second tier consists of every other bank. From large regionals to small community banks, depositors and investors simply aren’t sure what the rules for deposit insurance are.

Will the grace that was extended to Silic0n Valley and Signature Bank customers be extended to your bank if it is troubled? No one knows for sure. The Secretary of the Treasury, who was formerly the Chair of the Fed, has given conflicting answers. During Congressional testimony, she gave a particularly unsatisfying answer about whether a small community bank in Oklahoma would be important enough to protect. While that bank might not take down the entire financial system, the damage that could be done to its customers might be catastrophic.

This will remain an issue to be worked out by policy makers and regulators. The early results are encouraging but trust can disappear quickly as the depositors at Silicon Valley Bank learned. Our larger concern is a longer term one about the impact on the banking industry. Banks and bankers don’t often garner much sympathy, but the banking system is the economy’s circulatory system. If it isn’t functioning well, it is hard to have the economy overcome those problems in the same way that a heart patient has to get their heart healthy before they begin to exercise.

Jim Bianco has pointed out that the depletion of bank deposits began before the bank runs as customers have been increasingly frustrated with non‐existent or low returns on deposits. As the Fed raises rates, investors can now get returns of more than 4% on short‐ term Treasuries. Many banks continue to pay .01% on deposits. That disparity began the deposit withdrawals and a loss of faith in the stability of the banks accelerated it.

Banks could deal with this by increasing what they will pay for deposits. The trouble is that a move in that direction will mean a hit to bank profits. Whether it is narrow net interest margins, losses on loans, or losses on government securities because of interest rate hikes, all three negatively impact bank profits and the capacity of banks to lend.

That, in turn, will depress banker bonuses and force bank share prices lower. Some might be pleased by that account, but if the ability of banks to make loans is reduced, the knock‐on effects are critical. Regional and community banks are the key lenders for most commercial real estate and small business loans. Whether they are unable or unwilling to make loans doesn’t matter. The fact is that we have in just the past few weeks begun to see a sharp slowdown in credit provision. That is not good news for the economy.

Clearly, this development increases the possibility of a recession.

What does this mean for the markets?

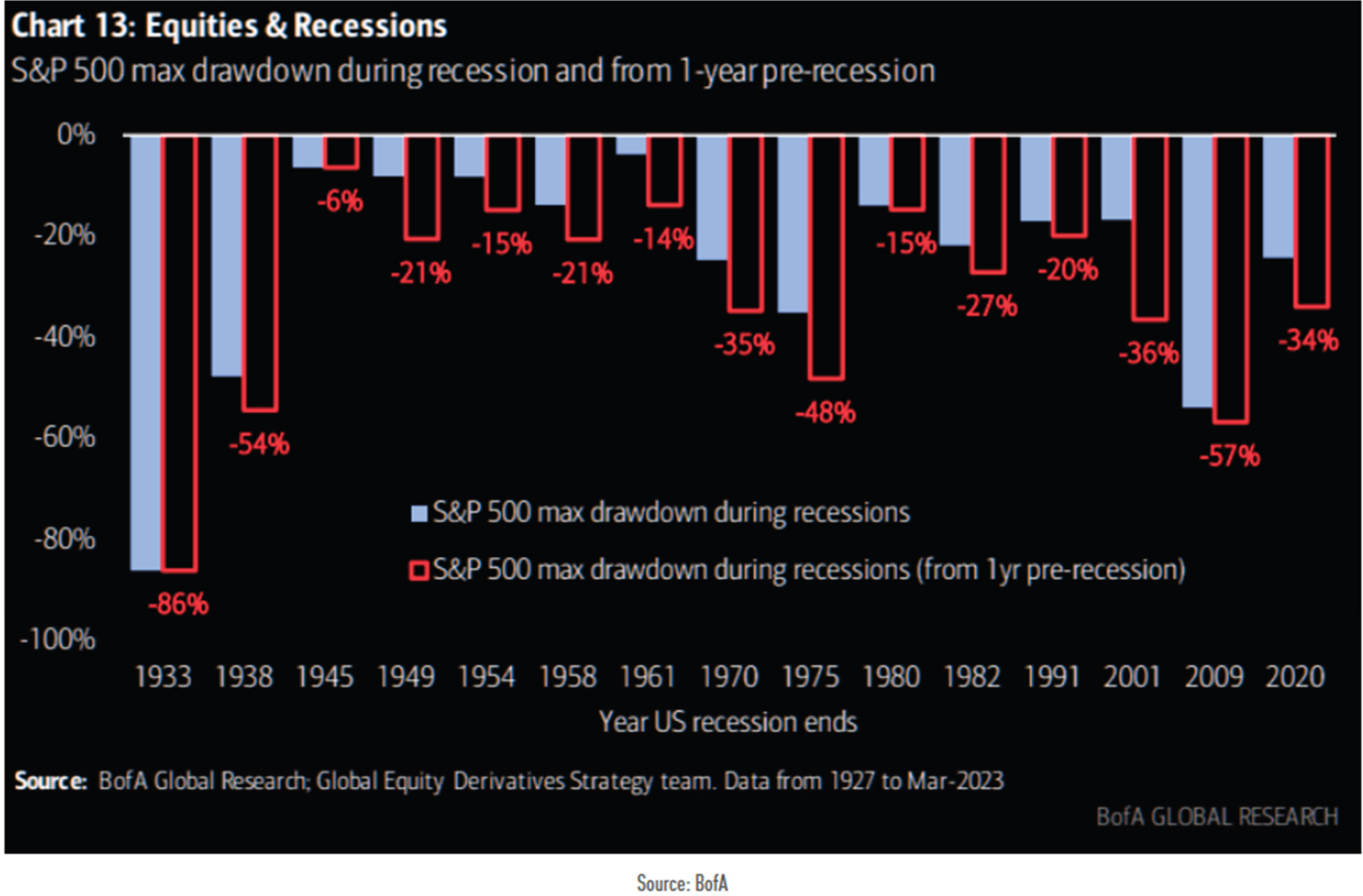

As we described last year when the US economy experienced two quarters of negative GDP growth (the technical definition of a recession), there is a significant difference between bear markets that occur outside of recessions and those that occur in conjunction with a recession. Non‐recessionary bear markets tend to be quick and shallow affairs. While 20% declines aren’t pleasant, the brief duration and often rapid recovery makes them more tolerable.

For recessionary bears, the decline in earnings can be 40% to 50%. This drives deeper price declines (averaging 38%) and longer lasting downturns. Obviously, it takes a stronger balance sheet and a higher pain threshold to ride out a recessionary bear market.

While the odds of a recession have gone up, it isn’t a given. In just the past week, GDP forecasts have actually been adjusted upward by the real time forecasts maintained at two of the Fed branches. Employment has softened but remains strong with unemployment at 3.5%. That is a level that is hard to square with an imminent downturn.

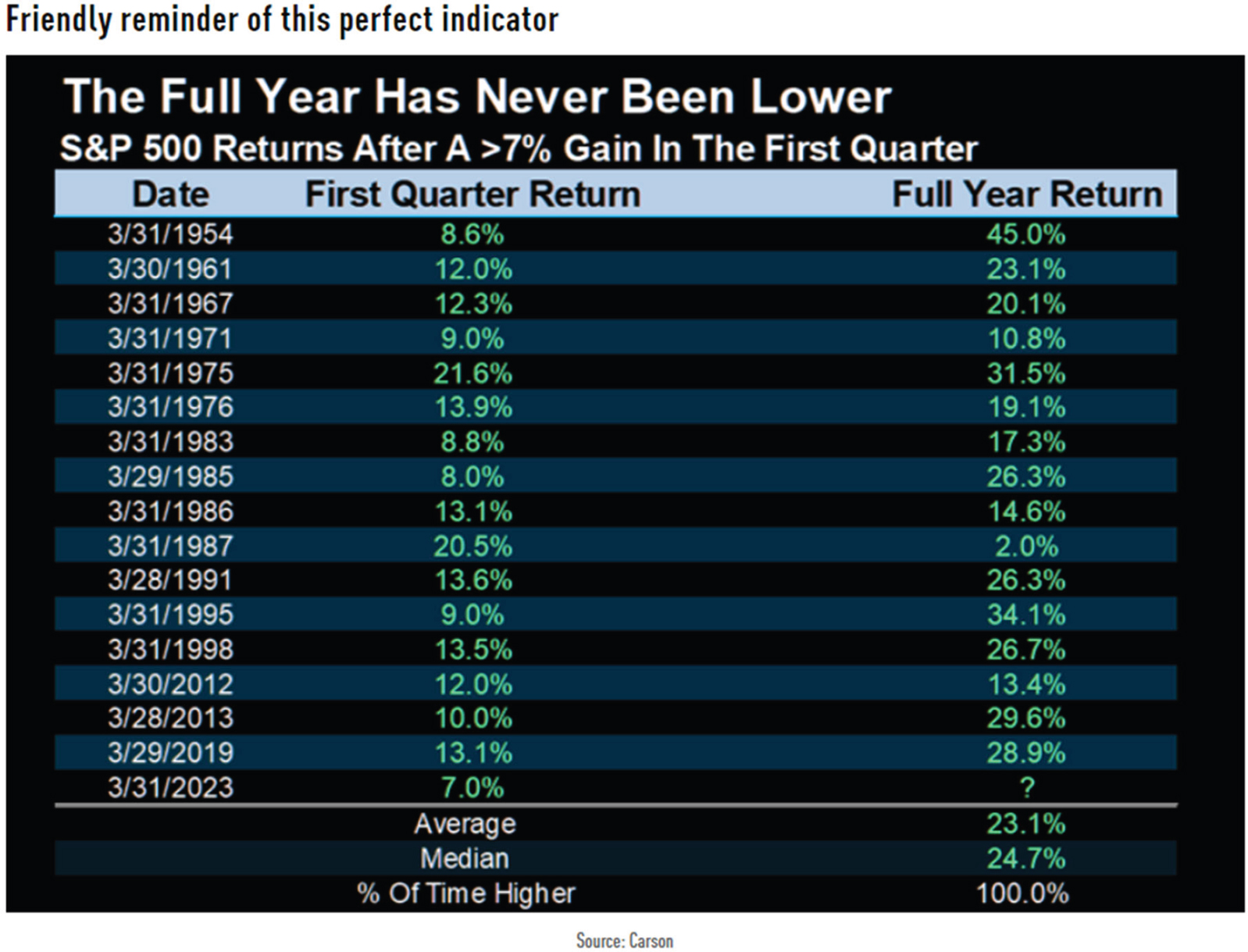

Of particular note is the resilience of stocks. We ended the quarter with US stocks up 7% as measured by the S&P. When an asset resists declines in the face of bad news, that can be a subtle but powerful signal of higher prices to come. To that end, when the market has been up 7% in the first quarter (not a real common occurrence) there has never been an instance that it was down for the year:

We respect markets and price discovery, so this data is important. Even with this confidence boost, we remain concerned about valuations and the narrow nature of the advance in tech. Despite the strong returns for mega cap tech stocks in the first quarter, technology looks absolutely and relatively expensive:

This doesn’t mean that you don’t own technology. It simply highlights yet again the importance of paying attention to value. The price you pay for an asset is the single largest determinant of how that asset will perform. That has always been the case and we believe it will remain the case. Our preference for cheap versus expensive assets is not changed by a single quarter or even a single year of outperformance by the expensive versus the cheap.

The other asset class getting attention today is commercial real estate. The lingering impact of the Covid 19 lockdowns on commercial real estate in general and offices in particular has focused attention on this asset class. Because loans on commercial real estate are a staple of regional and community banks, the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank has only exacerbated those concerns. There is a substantial amount of real estate debt to be refinanced in the next few years and with pressure on asset values and higher rates, there will be some stumbles along the way. It would appear to us, however, that much of that risk is well known and priced in the markets.

On balance, we remain defensive in our outlook and positioning. With higher short‐term interest rates, having a more defensive stance isn’t nearly as expensive as it once was. We are grateful for that and continue to seek opportunities as the markets ebb and flow.